“With crown and mace and disc, a mass of effulgence gleaming everywhere, I see thee so dazzling to the sight, bright with splendor of the fiery sun blazing from all sides — incomprehensible!” ~ Translated from Chapter 11, Verse 17, Bhagavad Gita

Introduction

Lipidologists regard elevated triglycerides (TG) as an enigma: Are they a biomarker of risk or a target of therapy to reduce cardiovascular events? The association between elevated triglyceride levels and cardiovascular disease (CVD) remains a mystery. The magnitude to which triglycerides embody a biomarker of risk has been contested for more than three decades. Furthermore, beyond lifestyle modifications and statin therapy, pharmacological treatments aimed at lowering triglyceride levels have been fraught with mixed results. The variables of low high-density lipoprotein (HDL), high low-density lipoprotein (LDL) and other emerging biomarkers — as well as the dynamic complexity of lipid metabolism — have confounded our treatment effects on hypertriglyceridemia. However, hypertriglyceridemia and triglyceride-rich lipoproteins seem to play a critical role in adverse global public health consequences, including atherogenesis, obesity, metabolic syndrome, diabetes, pancreatitis, and chronic kidney disease. This article will provide a brief overview of the current status of hypertriglyceridemia, not only addressing the scope of the problem but also reviewing opportunities to expand the current treatment strategies.

Scope of the Problem

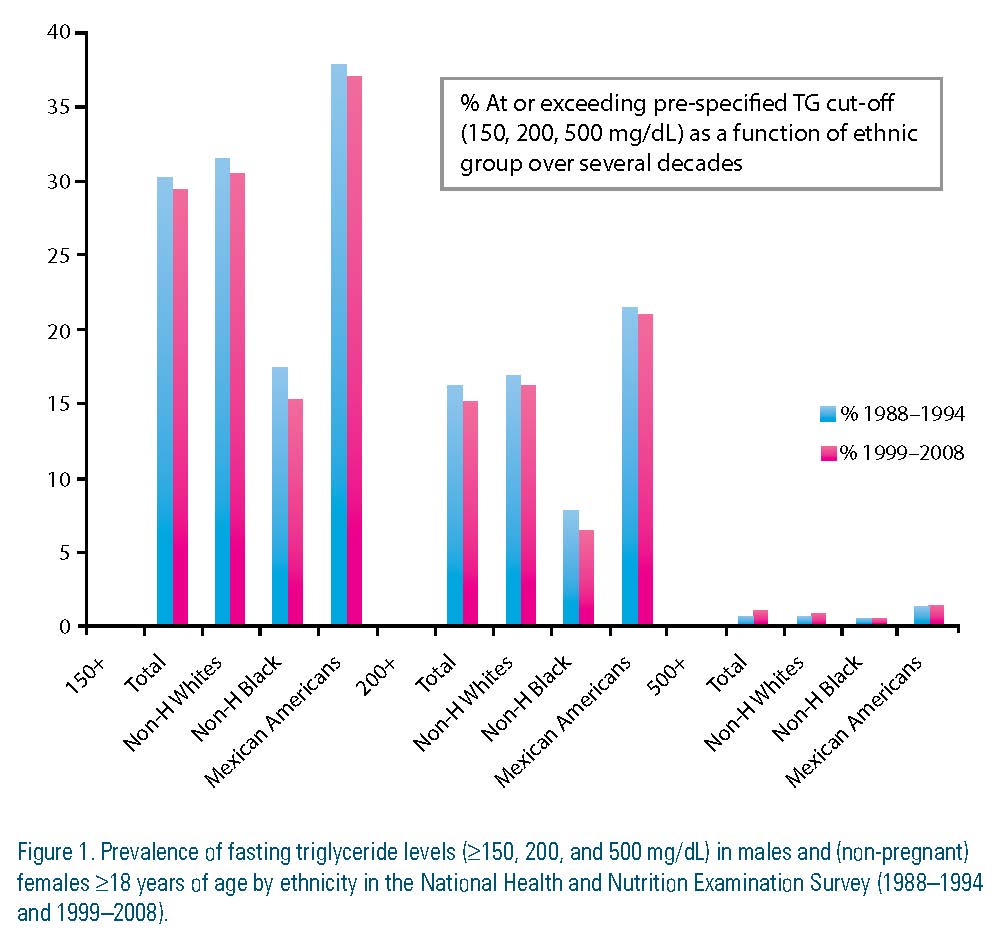

Hypertriglyceridemia levels are classified as: 150 to 199 mg/dL (borderline high); 200 to 499 mg/dL (high); and ≥500 mg/dL (very high).1 From the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data set, 31 percent of the adult U.S. population has a triglyceride level ≥150 mg/dL, a level unchanged since 1988. Among the various ethnic groups, Mexican Americans have the highest rates (34.9 percent), followed by non-Hispanic whites (33 percent), and blacks (15.6 percent), the lowest. In addition to the high prevalence, there are other factors that contribute to the degree of concern regarding hypertriglyceridemia.

First, measuring TG itself is an issue. Triglyceride levels are not normally distributed; hence, log transformation is favored over the arithmetic mean to reduce the potential impact of outliers. In addition, there is a strong inverse association with high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) and apolipoprotein AI (Apo AI), suggesting a complex biological relationship that may not reflect the effects in a multivariate analysis.

Secondly, in many case-control and angiographic studies, TG has been identified as a “risk factor” even after adjustment for total cholesterol, low- density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) and HDL-C.

Thirdly, prospective cohort studies demonstrate a univariate association of triglycerides with CVD that became non- significant after adjustment for either total cholesterol (TC) or LDL-C. Meta-analysis from the U.S. and Europe — including the Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration that evaluated 302,430 people free of known vascular disease at baseline in 68 prospective studies — demonstrated a strong, stepwise association with both CVD and ischemic stroke in univariate analysis; however, after adjustment for standard risk factors and for HDL-C and non–HDL-C, the associations for both CVD and stroke were no longer significant. Additional data from studies involving young men have provided new insight into the triglyceride risk status question. In 13,953 men ages 26 to 45 years old followed for more than 10 years, there were significant correlations between adoption of a favorable lifestyle, TG level, and CVD reduction.

Fourth, while the landmark randomized controlled trials with statins to reduce LDL-C have remained the principle treatment target for cardiovascular prevention, the Veterans Affairs HDL-C Intervention Trial (VA-HIT) showed that treatment using a fibric-acid derivative — with more marked effects on triglycerides (−31 percent) and HDL-C (+6 percent) and no effects on LDL-C — significantly reduced the relative risk of recurrent coronary heart disease in men ages ≤ 74 years without profoundly elevated LDL-C (mean = 111 mg/dl).

Fifth, there is a convincing case for targeting non HDL-C (a measure of atherogenic lipids that incorporates TG levels elevated in subjects with residual risk) to impede atherosclerotic progression and prevent cardiovascular events in patients with diabetic dyslipidemia.

In the analysis of the Get With the Guidelines database and United Kingdom General Practice Research Database, subjects with low HDL-C (< 40 mg/dl in men and < 46 mg/dl in women) and elevated triglycerides (≥ 150 mg/dl) had a 39 percent higher relative risk of cerebrovascular and cardiovascular events. In the Treating to New Targets (TNT) study, maximum-dose atorvastatin lowered the relative risk of major cardiovascular events by 22 percent (p < 0.001); however, statin recipients still had a 17.4 percent 10-year absolute risk of a first event. In addition, even among patients who achieved LDL-C levels < 70 mg/dl with high-dose statin therapy, those with the lowest HDL-C levels still had high residual cardiovascular risk.

In the European Prospective Investigation of Cancer (EPIC-Norfolk) study, the Women’s Health Study and the Strong Heart Study (SHS), non-HDL-C seems to play a bigger role. However, both the Heart Protection Study 2 — Treatment of HDL to Reduce the Incidence of Vascular Events (HPS2-THRIVE) and AIM – HIGH studies did not show benefits of niacin in improving CV events in subjects with low HDL. Finally, in the Expert Panel in the recent American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) cholesterol guidelines, no recommendations are made for or against specific LDL-C or non–HDL-C goals for the primary or secondary prevention of arteriosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD). These recommendations will be discussed further in this theme issue.

To summarize the scope of TG as target for therapy, the independence of triglyceride levels as a causal factor in promoting CVD remains contentious. Rather, triglyceride levels appear to provide distinctive information as a biomarker of risk, especially when combined with low HDL-C and elevated LDL-C. (Figure 1)

Triglyceride Metabolism

Triglyceride Metabolism

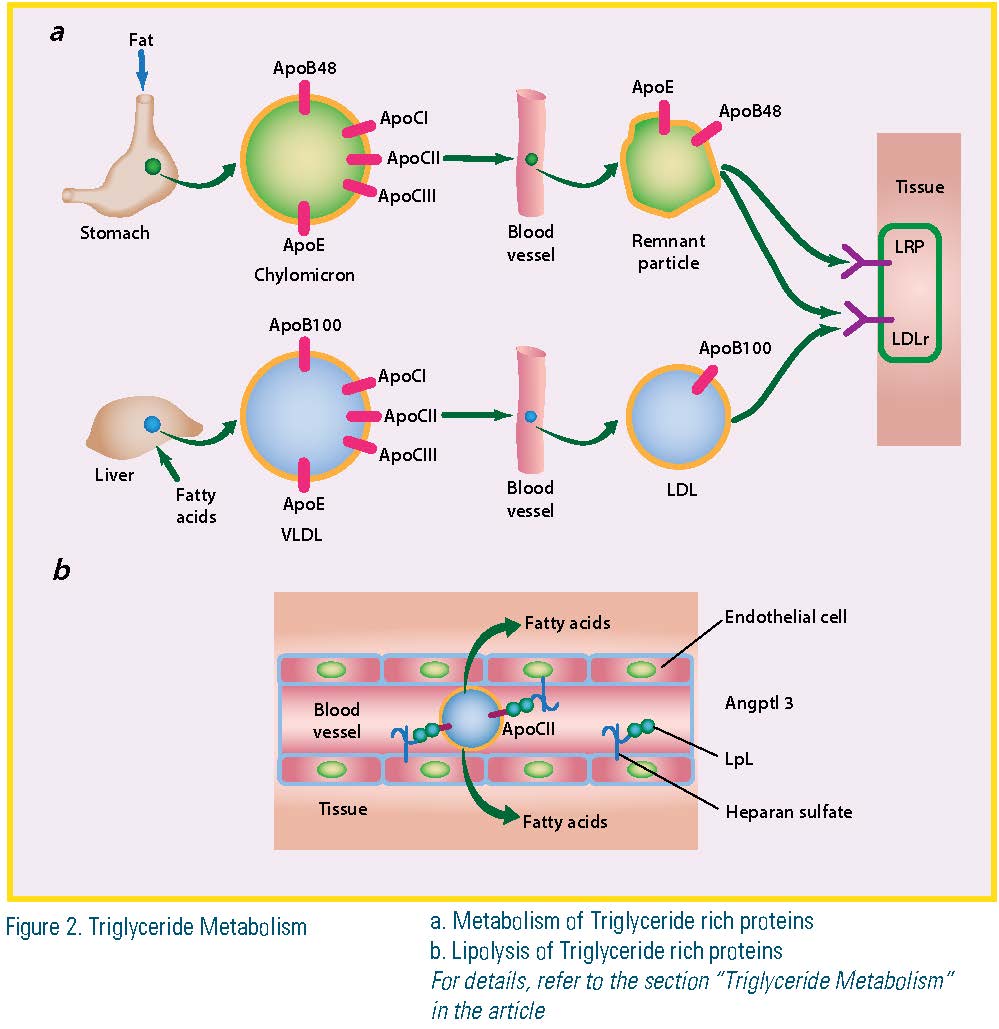

Chylomicrons and very low-density lipoproteins (VLDL) are the two classes of lipoproteins whose major lipid is triglyceride. Chylomicrons are formed in the intestine and their triglyceride is mainly derived from dietary fat. These particles initially are secreted into the lymphatics. Once in the bloodstream, much of the triglyceride is hydrolyzed into free fatty acid (FFA). The smaller, remnant particles are removed from the bloodstream by low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDLr) and lipid-rich plaque (LRP). Apolipoprotein E (Apo E) and Apo B are the ligands for these receptors. VLDL contains triglycerides assembled in the liver from the FFA or de novo-synthesized fatty acids. Some of these fatty acids are derived from adipose tissue when hormone-sensitive lipase is activated. VLDL triglyceride also is lipolyzed within the bloodstream and the remaining lipid — primarily cholesterol and cholesteryl ester — circulates as LDL. Apo B100, the major structural protein of LDL, contains a LDL receptor-binding region; apolipoprotein CI (Apo CI) and apolipoprotein CIII (Apo CIII) are smaller proteins that modulate lipolysis and interaction of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins (TRL) with receptors. The conversion of triglyceride to FFA occurs primarily within the capillaries. The fatty acids are then internalized and used for muscle energy or stored primarily within the adipose. The particles must interact with lipoprotein lipase (LpL) that is associated with heparan sulfate proteoglycans on the luminal surface of endothelial cells. LpL requires a co-enzyme, apolipoprotein CII (Apo CII), which is a component of both VLDL and chylomicrons. Apo CIII and perhaps other apolipoproteins inhibit the lipolysis reaction. ApoCIII containing TRLs contribute to atherogenesis. (Figure 2)

Factors Causing Hypertriglyceridemia

Multiple factors contribute to hypertriglyceridemia. Causes can include familial and inherited disorders, hypothyroidism, third-trimester pregnancy and poorly controlled diabetes with insulin deficiency. Medications such as interferon, antipsychotics, beta blockers, bile acid resins, estrogens, protease inhibitors, raloxifene, thiazide diuretics, retinoic acid, steroids, sirolimus, and tamoxifen also raise TG. Obesity, sedentary habits, diabetes, metabolic syndrome, alcohol excess, idiopathic urticarial, and chronic kidney disease also can be considered causes.

Treatment Strategies in Hypertriglyceridemia

Optimization of nutrition can result in a marked triglyceride-lowering effect that ranges between 20 and 50 percent. Strategies including weight loss, reducing simple carbohydrates (CHO), increasing dietary fiber, eliminating trans fatty acids, restricting fructose, and saturated fatty acids (SFA), implementing a

Mediterranean-style diet and consuming marine-derived omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) have proved successful.

However, dietary interventions also depend on the diagnosis. Inherited LPL and related disorders require fat restriction while many of the secondary causes require CHO restriction. Factors associated with elevated triglyceride levels include excess body weight, especially visceral adiposity; simple CHOs, including added sugars and fructose; a high glycemic load; and alcohol.

Published clinical trials so far have not been designed specifically to examine the effect of triglyceride reduction on CVD event rate. But secondary analyses from major trials of lipid intervention have assessed CVD risk in subgroups with high triglyceride levels. Unfortunately, most clinical trials limited entry triglyceride level to <400 mg/dL, and no known triglyceride- specific data from trials of diet and other lifestyle modifications are available.

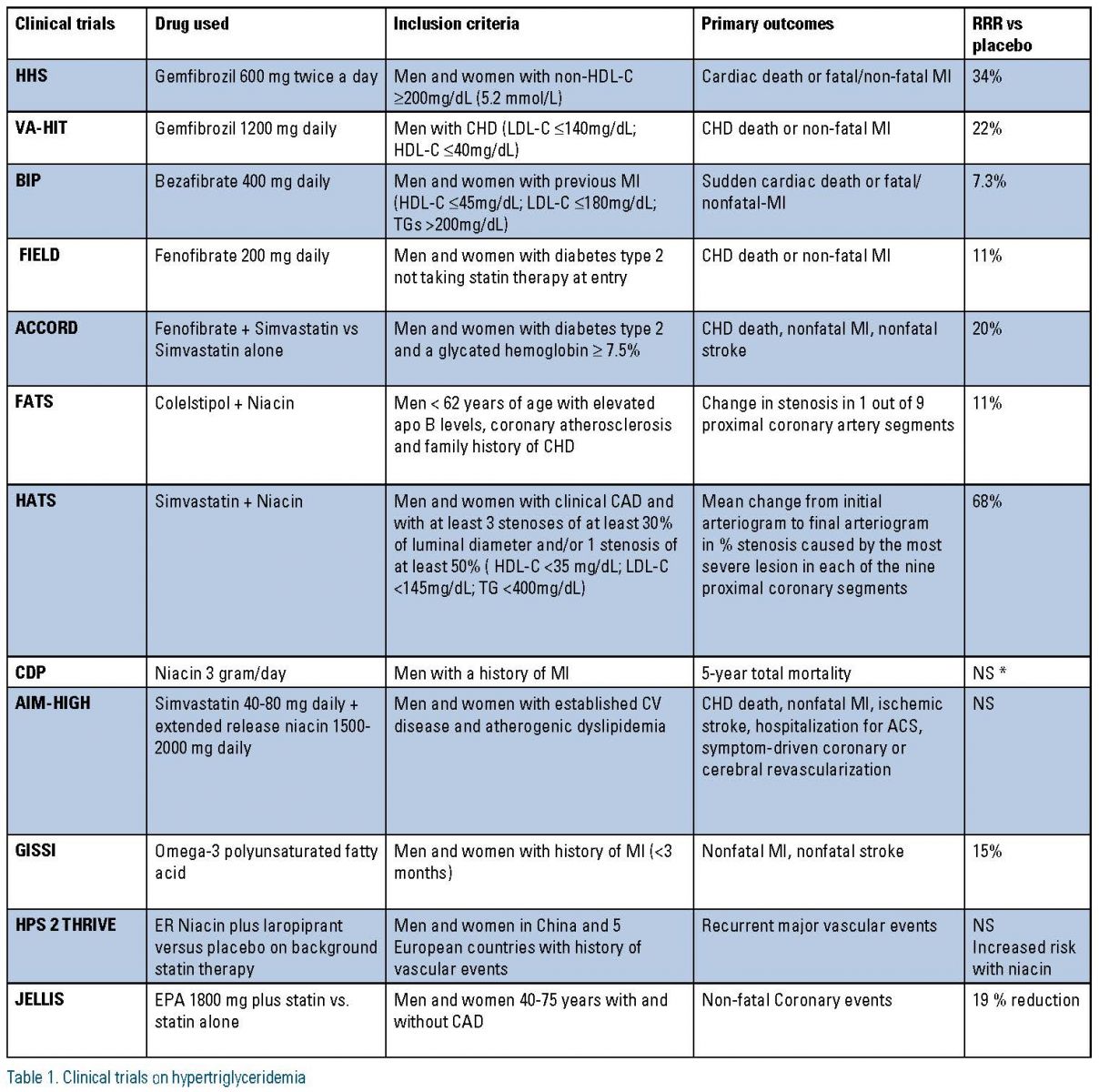

As monotherapy, fibrates offer the most triglyceride reduction, followed by immediate-release niacin, omega-3 FA, extended-release niacin, statins and ezetimibe. In statin trials, subgroups with increased baseline triglyceride levels were reported to have increased CVD risk in the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study (4S), Cardiac Angiography in Renally Impaired Patients (CARE), West of Scotland Coronary Prevention Study (WOSCOPS), Air Force/Texas Coronary Atherosclerosis Prevention Study (AFCAPS/TEXCAPS) and Treating to New Targets (TNT) studies and to have greater CVD risk reduction with lipid therapy in 4S and CARE. Thus, in patients with hypertriglyceridemia, statin therapy may be beneficial in the setting of high LDL-C levels. In addition, high-risk subgroups with high TG benefited in the Helsinki Heart Study, the Bezafibrate Infarction Prevention study, and the Fenofibrate Intervention and Event Lowering in Diabetes (FIELD) study.

In the VA-HIT, fibrate therapy reduced cardiovascular risk across all categories of baseline triglycerides. The recent Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes (ACCORD) trial, which did not show an overall benefit for fibrate therapy added to statin therapy in type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), did show benefit in the subgroup with elevated triglyceride levels (>204 mg/ dL) and low HDL-C (<34 mg/dL).

In summary, aggregate data suggest that statin or fibrate monotherapy may be beneficial in patients with high triglyceride levels, low HDL-C, or both. In the Pravastatin or Atorvastatin Elevation and Infection Therapy trial (PROVE- IT/ TIMI 22) and the Incremental Decrease in Endpoints Through Aggressive Lipid Lowering (IDEAL) trial, we have learned that high-risk statin-treated patients who continue to have elevated triglyceride levels display an increased risk for CVD, but these patients also have other metabolic abnormalities and adjustment for measures of these associated abnormalities, such non-HDL-C and Apo B, decreases the predictive effect of triglycerides.

In the Japan Eicosapentaenoic acid Lipid Intervention Study (JELIS), patients who received a statin plus eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) compared to statin alone reduced their CVD risk by 53 percent, even though the dose of EPA (up to 1.8 g/d) translated to minimal triglyceride reduction (5 percent between groups). However, subgroup analysis of primary prevention patients in JELIS indicated that patients with baseline triglyceride levels at or exceeding 150 mg/dL and HDL-C <40 mg/dL had significantly increased CVD risk. CVD risk reduction with combination therapy was not statistically significant in either baseline triglyceride subgroup (<151 or ≥151 mg/dL). Consequently, the cardiovascular benefit in JELIS was not a primary triglyceride-mediated effect. Also, trials that used statin plus niacin in AIM HIGH and HPS2 have not shown reduction in CV outcomes. (Table 1)

Summary

Hypertriglyceridemia is highly prevalent in patients with metabolic syndrome and studies have shown this to be an independent risk factor for developing CVD. The initial approach to treating hypertriglyceridemia is lifestyle and dietary changes and treating secondary causes of elevated TGs. When TG levels are still above 200 mg/dL but less than 500 mg/ dL after conventional treatment, the first- line pharmacological treatment is a statin to normalize LDL-C. Those patients with residual lipid abnormality may benefit from the addition of fibrates, especially gemfibrozil, niacin or omega-3 fatty acids. In addition to intensive therapeutic lifestyle change, utilizing triglyceride- lowering medications to prevent pancreatitis in those with triglyceride levels >500 mg/dL is reasonable. Whether these modalities favorably influence CVD outcomes beyond proven therapies (e.g., statins) remains an unproven hypothesis. Therefore, additional clinical outcome trials are necessary.

Disclosure statement: Dr. Vijay has received speaker honorarium from Aegerion, AstraZeneca, Amarin, Medtronic, and Otsuka, and consultant fees from Aegerion. He was on the advisory board for Amarin, a committee member with the American College of Cardiology, and was a principal investigator with Scottsdale Healthcare. Dr. Haffey has received speaker honorarium from Merck & Co., PCNA, and CSOM. He was a board member and part of the Quality Assurance Committee for the American College of Cardiology.

References are listed on page 33 of the PDF.

.jpg)

.png)