The principles of evidence-based medicine (EBM) initially were established to evaluate medical interventions.1,2 These same standards first were applied in the development of nutrition recommendations by the Institute of Medicine for the 1997 Dietary Reference Intakes and, soon thereafter, by the Dietary Guidelines for Americans in 2005.3,4 Nutrition science clearly has benefited from becoming more rigorously evidenced-based, using better study designs and statistical analyses in the past 20 years.

Nevertheless, performing research in nutrition and interpreting results from nutrition studies is much more complex than it is in the pharmaceutical world, and certain principles of evidenced- based medicine are not as applicable in nutrition research.5-7 Listing just a few of the differences should make this apparent: 1) Most drugs are single compounds, manufactured with uniform consistency, and have comparatively narrow physiologic effects. Food is composed of numerous (micro- and macro-) nutrient components, with potential synergistic (and antagonistic) interactions when consumed; their effects are altered by growing conditions, the food matrix (non-nutritive components of the food), processing, preparation and the host’s gut microbiome. 2) Drug effects are studied against a non-exposed (placebo) control group, whereas every dietary control group has at least some “exposure” to the nutrient(s) being tested, the degree of which can profoundly affect the outcome of the study. 3) Drug studies are designed to reduce incidence of a disease not caused by their absence and to show efficacy in a relatively short period of time. Nutrients prevent dysfunction that would result from their inadequate intake and may require decades to demonstrate their impact.

One of the maxims of EBM is that the result from a randomized, placebo- controlled trial (RCT) is the highest level of evidence, but RCTs often are not the most appropriate or feasible study design to answer questions about the long-term effects of consuming specific foods or nutrients, unless they can be packaged in a pill.8,9

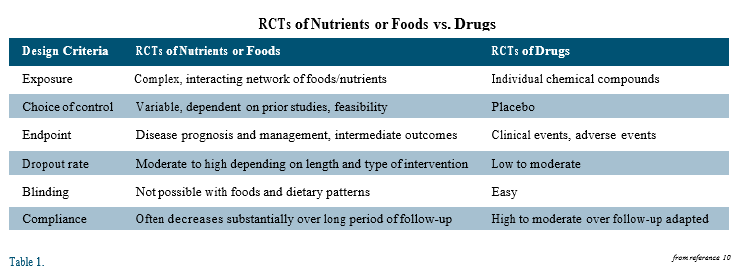

There are several important differences between RCTs in pharmaceutical and nutritional research. Unlike drug or supplement trials, RCTs of dietary interventions cannot be blinded; knowledge of treatment assignment has the potential to alter participants’ behavior in a way that may influence the clinical outcome of interest and, thus, reduce confidence that any difference in outcome is because of the assigned intervention. Dropout rates also usually are higher in nutrition RCTs than in drug trials, being directly proportional to the length of the trial and the complexity of the dietary intervention. Nonadherence to the assigned diet is another major problem in trials of long duration and complexity. For all of these reasons and more (see Table), nutrition RCTs frequently cannot answer their original study question.10

The two largest and most famous dietary RCTs for cardiovascular disease (CVD) prevention in the past decade illustrate the challenges. The Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) was designed to test the hypothesis that a dietary pattern low in fat and high in vegetables, fruits and grains would reduce breast and colorectal cancer, with incidence of cardiovascular (CV) events as a secondary endpoint.11 Over a mean follow-up of 8 years, there was no difference in the incidence of coronary heart disease (CHD), stroke or CVD; however, most participants assigned to the low-fat group were unable to achieve the total fat intake target of 20% of calories (at year 6 mean % energy from total fat: 29% for intervention arm vs 37% for control; saturated fat: 9.5% vs 12.4%). The WHI, therefore, failed to test its original hypothesis and even raised the question of whether reducing saturated fat by a moderate amount has any impact on the risk of CV events.12 A similar outcome occurred in the Prevención con Diets Mediterránea, or Prevention with Mediterranean Diet (PREDIMED) study, which was designed to test the hypothesis that a supplemented Mediterranean diet compared to a healthy low-fat diet would reduce the incidence of major cardiovascular events.13

The supplements used in this RCT were extra-virgin olive oil (EVOO) in one Mediterranean diet group, and mixed nuts in a second Mediterranean diet group, while the control group only received advice to reduce dietary fat. The trial was halted, based on interim analysis, after a median follow-up of 4.8 years, because of a 30% reduction in cardiovascular events in each of the supplemented Mediterranean diet groups compared to the control group. However, despite efforts to the contrary, the control group did not achieve even a moderate reduction in fat intake (at end of trial, % energy from total fat: 41% for Mediterranean diet groups vs 37% for control; saturated fat: ~9% for all 3 groups). Dietary advice led to a modest difference in legume and fish consumption in the Mediterranean diets groups compared to the control, but intake of all other non-supplemented foods was the same. The only major dietary difference between groups was because of the supplemental foods.

Therefore, the PREDIMED trial essentially was a test of three Mediterranean diets, differing primarily (but not exclusively) in type and amount of olive oil and nuts.14 Thus, the study results raise several important questions: Will 4 tablespoons of EVOO (or 30 gm nuts) a day enhance the CV benefits of a healthy American diet? Will improvements in a Mediterranean- style dietary pattern (i.e. increases in a Mediterranean diet score*) without high intake of EVOO or nuts reduce CV events?

It has become a truism in nutrition science that recommendations must be made based on the “totality of evidence” from the best available studies, i.e. prospective cohort studies with clinical outcomes, short-term intervention trials with physiologic endpoints, and well-executed RCTs. When results are corroborative among different types of research, we can have confidence in our recommendations. When the results are not as consistent or there are quality concerns, we have to live with more uncertainty, be less dogmatic with our recommendations and patiently wait for more data. In the meantime, we need to educate our patients that nutrition science generally has reached consensus, certain issues notwithstanding, on what foods and dietary patterns do (and do not) comprise a healthy diet.

*Mediterranean diet scores are short food intake questionnaires (usually 10-14 items) used in nutritional epidemiology studies to quantify how closely an individual adheres to what the authors define as a Mediterranean diet. In the PREDIMED study the difference in their 14-point score between the Mediterranean diet groups and the control diet group ranged from 1.4 to 1.8 points over the course of the study.

Disclosure statement: Dr. Barringer has received honoraria from Amgen and Regeneron.

References are available here.

.jpg)

.png)