Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) contributes to cardiovascular disease risk through dyslipidemia, insulin resistance, altered coagulation states, and increased inflammation. NAFLD occurs in greater than 25% of individuals worldwide. Its prevalence is highest in the U.S. Hispanic population, followed by White and Black individuals.1 The incidence is twofold greater in men compared with women.1 The purpose of this article is to highlight the key points from the recently published AHA scientific statement on NAFLD and cardiovascular risk.8

NAFLD is characterized by a spectrum of conditions that range from hepatic steatosis to more advanced stages, such as nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) and hepatic cirrhosis. NAFLD may be further defined as hepatic steatosis in the absence of excess alcohol intake or other causes of secondary or monogenic hepatic steatosis.3 NASH requires the presence of hepatic steatosis in addition to histological evidence of hepatocellular inflammation and cell death. NAFLD is associated with visceral adiposity, atherogenic dyslipidemia, and insulin resistance.

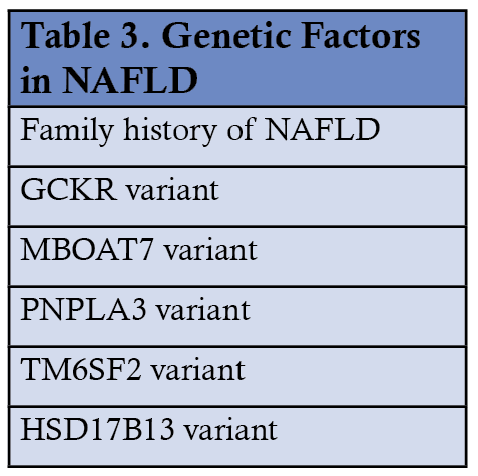

A constellation of risk factors contributes to the development of NAFLD/NASH. These are summarized in tables 1-3. Endocrine abnormalities such as insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes, visceral obesity, and metabolic syndrome are major contributors. In the setting of insulin resistance, the lack of suppression of hormone-sensitive lipase in adipocytes leads to increased lipolysis of triglycerides and release of fatty acids. The excess load of fatty acids overwhelms the liver's capacity to eliminate them through oxidative processes, VLDL assembly, and gluconeogenesis, thus leading to the development of cytosolic fat droplets and hepatic steatosis. Other risk factors for the development of NAFLD include chronic kidney disease,4 polycystic ovarian syndrome,5 familial hypobetalipoproteinemia, and drugs (like amiodarone, lomitapide, valproic acid, reverse transcriptase inhibitors, corticosteroids). Genetic factors play a role in the development of NAFLD. Polymorphisms in glucokinase regulatory protein (GCKR), membrane-bound o-acyltransferase domain containing 7 (MBOAT7), patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing protein 3 (PNPLA3), transmembrane six superfamily member 2 (TM6SF2) increase the risk. At the same time, variants in 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 13 (HSB17B13) are associated with protection from NASH.

NAFLD appears to be an independent risk factor for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) even after adjustment for other covariates.6 NAFLD can be considered a risk enhancer when ASCVD risk is assessed in patients. Patients with NAFLD who undergo coronary artery bypass graft surgery may have poor outcomes. ASCVD is the principal cause of death in patients with NAFLD.7

NAFLD is often underdiagnosed. NAFLD fibrosis score and fibrosis-4 index are simple risk prediction tools that help predict the presence of fibrosis. Imaging options for diagnosis include ultrasound, CT, and MR imaging. Ultrasound is less expensive but lacks sensitivity. CT, MRI, and MR spectroscopy have progressively higher sensitivity and specificity for detecting steatosis but are less accurate in detecting fibrosis and steatohepatitis. Vibration-controlled transient elastography (FibroScan™) is an ultrasound-based modality better for assessing liver fibrosis. Liver biopsy remains the gold standard for diagnosis.

The goals of treatment of NAFLD and NASH are the same and are three-fold:

- To preserve liver function and prevent the progression of liver disease.

- To prevent and treat metabolic complications such as diabetes and metabolic syndrome.

- To reduce cardiovascular risk through lifestyle modification, including regular exercise and a heart-healthy, low-fat, low-glycemic index diet. This remains the cornerstone of treatment

Weight loss of as little as 5% can significantly decrease hepatic fat. Restricting high-fructose corn syrup to less than 20 g/day improves NASH without weight loss9. Following a Mediterranean diet and abstaining from alcohol improves NASH. Drugs like pioglitazone, GLP-1 agonists (liraglutide, semaglutide), and metformin (low certainty evidence) which will improve diabetes, can also improve NASH. Novel experimental drug therapies are in development, but most have modest efficacy, and toxicity is a limiting factor. There are no FDA-approved medications to treat NAFLD/NASH at this time.8

References

- Younossi ZM, Koenig AB, Abdelatif D, Fazel Y, Henry L, Wymer M. Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: meta-analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence, and outcomes. Hepatology. 2016;64:73–84. doi: 10.1002/hep.28431

- Pan JJ, Fallon MB. Gender and racial differences in nonalcoholic fatty liverdisease. World J Hepatol. 2014;6:274–283. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v6.i5.274

- Chalasani N, Younossi Z, Lavine JE, Charlton M, Cusi K, Rinella M,Harrison SA, Brunt EM, Sanyal AJ. The diagnosis and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: practice guidance from the American Associationfor the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology. 2018;67:328–357.

- Yasui K, Sumida Y, Mori Y, Mitsuyoshi H, Minami M, Itoh Y, Kanemasa K,Matsubara H, Okanoue T, Yoshikawa T. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis andincreased risk of chronic kidney disease. Metabolism. 2011;60:735–739.doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2010.07.022

- Tan S, Bechmann LP, Benson S, Dietz T, Eichner S, Hahn S, Janssen OE,Lahner H, Gerken G, Mann K, et al. Apoptotic markers indicate nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in polycystic ovary sydrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab.2010;95:343–348. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-1834

- Targher G, Bertolini L, Padovani R, Rodella S, Tessari R, Zenari L, Day C,Arcaro G. Prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and its associationwith cardiovascular disease among type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care.2007;30:1212–1218. doi: 10.2337/dc06-2247

- Targher G, Day CP, Bonora E. Risk of cardiovascular disease in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1341–1350. doi:10.1056/NEJMra0912063

- Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and cardiovascular Risk: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association P. Barton Duell, MD, Chair; Francine K. Welty, MD, Vice Chair; Michael Miller, MD; Alan Chait, MD; Gmerice Hammond, MD, MPH; Zahid Ahmad, MD; David E. Cohen, MD, PhD; Jay D. Horton, MD; Gregg S. Pressman, MD; Peter P. Toth, MD, PhD; on behalf of the American Heart Association Council on Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis and Vascular Biology; Council on Hypertension; Council on the Kidney in Cardiovascular Disease; Council on Lifestyle and Cardiometabolic Health; and Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2022;42:e168–e185. DOI: 10.1161/ATV.0000000000000153

- El-Agroudy NN, Kurzbach A, Rodionov RN, O’Sullivan J, Roden M, Birkenfeld AL, Pesta DH. Are lifestyle therapies effective for NAFLD treatment? Trends Endocrinology Metabo. 2019; 30:701-709. doi:10.116/j.tem.2019.07.013

Disclosures:

Dr. Dharmesh Patel has earned consulting fees from Amgen, Janssen & Janssen, Boehmer Inghelhiem, Astra Zeneca, and Esperion.

Dr. Deepak Vedamurthy has no financial relationships to disclose.

Article By:

Stern Cardiovascular Foundation

Memphis, Tennessee

University of Pennsylvania

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

.jpg)

.png)