The approach to understanding hypercholesterolemia, hypertriglyceridemia, or both, starts with consideration of the underlying lipoprotein abnormalities present.1,2 This is followed by asking to what degree genetic or acquired causes explain the observed abnormalities. Since those with lipoprotein abnormalities and increased risk for either atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) or pancreatitis are candidates for drug therapy, finding acquired causes and instituting lifestyle changes could spare drug treatment or, at a minimum, reduce the intensity of such treatment. We present an informative case to illustrate issues related to secondary hyperlipidemia where a search for the cause and not pharmacotherapy is the primary approach.

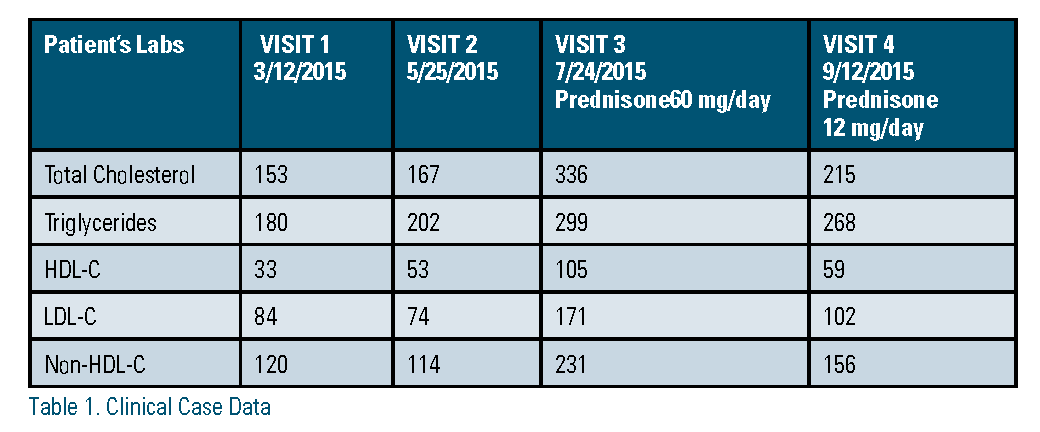

Case 1. A 43-year-old man with a history of minimal-change kidney disease and type 2 diabetes had been off steroid therapy for almost one year. Because of his diabetes, he was given atorvastatin 10 mg daily. He developed chronic clostridium difficile (CD) infection and required a fecal microbial transplant. This led to acute worsening of his nephrotic syndrome and high-dose prednisone therapy (60 mg/day). Cautioned to avoid weight gain, he presented to a lipid clinic with minimal weight change but elevated cholesterol and triglyceride, raised high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), and elevated low- density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), and non-HDL-C (Table 1). Concerned, he asked to discuss his treatment options.

Yet the recent onset of his hyperlipidemia and his complicated medical history made consideration of secondary causes crucial. A report from a lipid specialty clinic noted that the most frequently encountered secondary causes of hyperlipidemia included excessive alcohol intake, uncontrolled diabetes, and overt albuminuria.3 Recent guidelines list secondary causes of hyperlipidemia often encountered in clinical practice (Table 2).1 The patient was advised to adhere to a healthy lifestyle by increasing his activity level and decreasing his caloric intake. His statin dosage was not changed. Over the next month, his prednisone was tapered from 60 mg to 14 mg daily. Two months later, his repeat lipid panel had significantly improved. His lipid improvements were attributed to the resolution of his acute episode of nephrotic syndrome, decreased steroids, and improved lifestyle and weight control. He did not wish further lipid medications and indicated he wished to work further on lifestyle changes with the hope of improving his lipid measurements.

As part of the clinical discussion before lipid medication is given, it is essential to review secondary causes of hyperlipidemia. Although thyroid may be more common, both renal- and liver-associated lipid abnormalities illustrate the importance of pausing to find a secondary cause. One renal cause is nephrotic syndrome. This often is accompanied by elevated LDL-C, triglycerides, and lipoprotein(a), and normal or decreased HDL-C.4 The mechanism underlying abnormal lipid levels includes increased hepatic synthesis of apoproteins B, C-II and E, but without increased production of apoproteins A-I and A-II.5,6 These metabolic derangements lead to markedly elevated cholesterol levels. In a cohort of 207 nondiabetic patients with nephrotic syndrome, the LDL-C was noted to average 208 mg/dl.7 Such a marked elevation in the LDL-C could prompt an initiation of a high- intensity statin per the current 2013 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) guidelines.1 But high-intensity statin therapy may not be immediately required if the mechanism of increase in LDL-C is reversible5 and can resolve with specific treatment of the underlying causes of nephrotic syndrome. This is reflected in recommendations by the Kidney Disease International Global Outcomes (KDIGO) guidelines for treatment of nephrotic syndrome. KDIGO supported our management with a weak recommendation for not initiating statin therapy for minimal-change disease when clinical resolution with normalization of the lipid profile is likely.8

Although space limitations preclude another case, clinicians also should be aware of liver-related causes of elevated lipids. For example, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) may be accompanied by the atherogenic lipid triad of high triglycerides, elevated small dense LDL,9 and a low HDL-C.10 These lipid derangements are associated with increased ASCVD risk.11 This requires an initial focus on lifestyle change with subsequent consideration of statin use. In the setting of stable liver disease, NAFLD itself is not a contraindication to statin therapy.12 Primary biliary cholangitis, on the other hand, alters cholesterol metabolism by causing reflux of biliary lipids into the circulation and downregulation of lethicin-cholesterol acetyltransferase (LCAT) activity,13 resulting in an increase in triglycerides, LDL-C, and HDL-C (although HDL-C decreases with disease progression). However, the elevation in LDL-C is driven by the accumulation of lipoprotein-X, a lipoprotein that is resistant to in-vitro oxidation and which some believe may protect against atherogenesis.14 Thus, lipid derangements secondary to cholestasis may not increase ACSVD risk.15,16

Finally, medications may cause secondary elevations of lipids. We offer the following list of medications that can affect lipids. Most drug effects are mild but the drugs that greatly raise triglycerides can lead to pancreatitis.2 Often, it may be especially useful to focus on lifestyle interventions to minimize the effects on lipids. We suggest a mnemonic (ABCDEFGHI) for remembering frequently encountered classes of medications that affect lipids (Table 2).

Conclusion: The new cholesterol guidelines were notable for providing guidelines that focus on defining at-risk clinical groups, prioritizing interventions supported by strong evidence, and recommending clinician-patient risk discussions in lower-risk primary prevention before statin assignment despite the risk score. They advised the need to consider secondary causes of lipid abnormalities before assuming that lipid changes were primary. Identification of secondary causes whether they be medication, dietary, or related to diseases or disorders of metabolism is crucial before pharmacotherapy for lipids is given. Importantly, patients also may benefit from intensive lifestyle counseling to mitigate many changes in lipid parameters that can accompany secondary causes. Thus, when you see abnormal lipids, remember to search for a secondary cause(s); it’s worth the pause.

*Written permission was obtained from the patient.

Disclosure statement: Dr. Ducharme-Smith has no disclosures to report. Dr. Laczay has no disclosures to report. Dr. Raygor has no disclosures to report. Dr. Stone was the lead author of the 2013 ACC/AHA Cholesterol Guidelines.

References are listed on page 45 of the PDF.

.jpg)

.png)