Introduction

Solid organ transplantation (SOT), encompassing kidney, liver, heart and to a lesser extent pancreas and lung, has become routine care for optimal treatment of end-stage disease in many patients.1,2 Refinements in transplantation protocols have helped preserve transplanted organs while avoiding post-transplantation morbidity and mortality. Improved longevity in this population has shifted the focus from preservation of the transplanted organ to management of long-term outcomes. Data from multiple studies have demonstrated a significant burden of incident cardiovascular disease (CVD) post-transplantation, resulting in CVD being one of the leading causes of long-term morbidity and mortality in SOT patients.2,3 Risk factors for CVD post-transplantation are multifactorial consisting of pre-existing conditions (such as atherosclerotic CVD [ASCVD], end-stage renal disease, hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, etc), as well as cardiovascular toxicity and transplant vasculopathy secondary to immunosuppression. Treatment of dyslipidemia, primarily with statins, is an essential component of prevention and management of CVD after SOT. This review will focus on management of statin therapy after transplantation, with a focus on maximizing patient safety through careful management of drug-drug interactions.

Dyslipidemia in SOT Patients

Dyslipidemia has been identified in upwards of 80% of patients after SOT,1,3,4 which often necessitates treatment with a statin, but management of lipid-lowering therapy in these high-risk patients is complicated by concerns about drug-drug interactions. In the case of heart transplantation, severe dyslipidemia resulting in end-stage ischemic cardiomyopathy is the underlying basis for the transplantation in some patients, often necessitating an aggressive multidrug lipid-lowering drug regimen that is more complicated in the context of life-long immunosuppressant therapy post-transplantation. In some cases, immunosuppressant drugs themselves may also aggravate the dyslipidemia, further complicating efforts to achieve lipid goals. 5-12

Overview of Statin Therapy in SOT Patients

Although it is well documented in the general population that dyslipidemia causes CVD, and reductions in low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) translate into reduced CVD morbidity and mortality, the contribution of dyslipidemia to posttransplant CVD is not as well established. Statins are the most studied and efficacious class of medications in SOT patients. The most robust data demonstrating the benefits of treating dyslipidemia in SOT patients comes from studies of patients after heart transplantation. In this population, statin therapy, primarily pravastatin, simvastatin and atorvastatin, has consistently been shown to reduce the incidence of cardiac allograft vasculopathy and cardiac rejection, as well as improve survival.13 As a result, statin therapy is the standard of care in all post-heart transplant patients (Class I, level of evidence A).14 In kidney transplant recipients, the data are less robust, but guidelines from the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) lipid management group recommended statin therapy in all renal transplant patients (Grade 2A, [suggested, high quality of evidence]).15 There are no formal guidelines for statin therapy in liver, lung or pancreas transplant patients, but limited data suggest that statins may reduce rates of rejection, graft loss, and post-operative complications. 1,16,17

Potential Benefits of Altering the Immunosuppressant Regimen

When considering therapeutic management strategies, the first step is to consider whether a change in dyslipidemia-inducing immunosuppressant medication(s) would be both safe (without placing patient at risk for organ rejection) and beneficial. Preservation of the transplanted organ is essential, so transplant providers are often reluctant to make changes in the immunosuppressant regimen, but some alternatives can be considered. Options include minimizing the dose of corticosteroids, switching from cyclosporine to tacrolimus, and/ or discontinuing mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitors (sirolimus, everolimus) therapy—all of which may result in substantial reductions in lipoprotein concentrations.18

Interactions Between Statins and Immunosuppressant Drugs

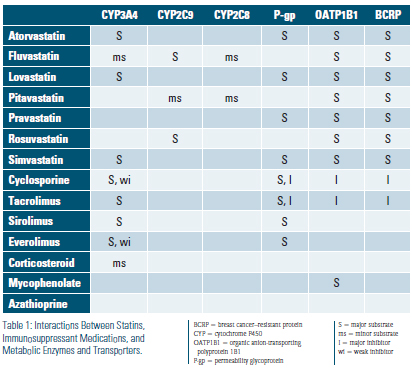

Drug-drug interactions are a major consideration in the selection of appropriate lipid-lowering therapy in SOT patients. Statins as a class are metabolized through several pathways that involve cytochrome (CYP) P450 enzymes, permeability glycoprotein (P-gp; also known as multidrug resistance-1), organic anion-transporting polyprotein 1B1 (OATP1B1) and breast cancer–resistant protein (BCRP), which are important enzyme and transporter systems for drug metabolism and elimination. Atorvastatin, lovastatin and simvastatin are substrates for the CYP P450 3A4 while other statins (pitavastatin, fluvastatin, rosuvastatin) undergo biotransformation via the less commonly utilized CYP 2C9 enzyme or completely avoid CYP P450 metabolism altogether (pravastatin). Of note, CYP metabolism (2C9 and to a lesser extent 2C8) plays a minor role in pitavastatin biotransformation. Atorvastatin, lovastatin, pravastatin and simvastatin are substrates for P-gp. All statins are substrates for OATP1B1 and BCRP.4,19 Co-administration of drugs metabolized through the same CYP P450 enzyme can substantially increase statin exposure in some cases. Statins are also metabolized in part by hepatic glucuronidation, but this catabolic pathway does not appear to be involved in adverse drug interactions with immunosuppressant medications. Immunosuppressant medications can interfere with multiple aspects of statin transport and metabolism. Calcineurin inhibitors are major substrates for CYP3A4, substrates for and inhibitors of P-gp, and inhibitors of OATP1B1 and BCRP. Cyclosporine is also a weak inhibitor of CYP3A4. The mTOR inhibitors (sirolimus and everolimus) are major substrates for CYP3A4 and P-gp and everolimus is also a weak inhibitor of CYP3A4. Azathioprine, mycophenolate and corticosteroids do not appear to significantly interact with these pathways. A summary of enzyme/transporter effects between statin and immunosuppressant medications is provided in table 1.

Most of the documentation of adverse drug interactions of immunosuppressant medications with statins comes from early clinical use of cyclosporine. The very first awareness of statin-cyclosporine muscle toxicity occurred in 1987 (the same year the first statin was FDA-approved) when rhabdomyolysis was identified in a heart transplant patient who was treated with lovastatin 40 mg BID in combination with cyclosporine, resulting in a 5-fold increase in the peak plasma concentration of lovastatin.20 Administration of cyclosporine in combination with statin therapy has been reported to increase statin total drug exposure by 2-20 fold. The most severe interactions were noted with lovastatin, pitavastatin and simvastatin, resulting in the warning that co-administration of these drugs with cyclosporine should be avoided. In addition, FDA labeling also recommends avoiding use of atorvastatin in combination with cyclosporine, but this is in contrast to scientific statements suggesting that a dosing limit of 10 mg for atorvastatin may be acceptable on the basis of data from pharmacokinetic studies. Recommended dosing limits for the remaining statins, fluvastatin, pravastatin and rosuvastatin when used concurrently with cyclosporine are 40 mg, 40 mg and 5 mg respectively. Since cyclosporine, tacrolimus and mTOR inhibitors share similar metabolic pathways that may negatively impact statin metabolism, one would expect comparable risk of adverse drug interactions with all of these immunosuppressant medications. For this reason, it has been recommended to implement dosing limits for statins used in combination with tacrolimus and mTOR inhibitors that are the same as the limits for use in combination with cyclosporine.4,18 Despite the logical recommendation to limit the dose of statins in combination with other immunosuppressants the same as for cyclosporine, there is uncertainty about whether the recommended dosing limits are unnecessarily restrictive.4 For example, rosuvastatin has been well tolerated in SOT patients at doses up to 20 mg daily, suggesting that doses higher than the recommended maximal dose of 5 mg daily may be safe in some patients.21 In addition, administration of tacrolimus in combination with atorvastatin or simvastatin has not been demonstrated to cause significant changes in statin accumulation or adverse effects, suggesting that higher doses of atorvastatin and simvastatin may be acceptable in combination with tacrolimus compared to cyclosporine.22,23 Although mTOR inhibitors may increase the post-dose plasma statin area under the curve, the lack of an inhibitory effect of mTOR inhibitors on OATP1B1 and BCRP suggests that less significant interactions with statins may be anticipated compared to the effects of cyclosporine. Further studies are needed to verify whether higher doses of statins can be safely used in combination with tacrolimus or mTOR inhibitors, but in the meantime cautious use and close monitoring is advised should the clinician choose to exceed the dosing limits imposed on the basis of the cyclosporine interaction literature. It is important to also be aware that calcineurin and mTOR inhibitors are independently associated with increased risk of muscle toxicity, further compounding the potential risk for muscle toxicity in combination with statin therapy.

Strategies for Choosing an Appropriate Statin Regimen

he decision regarding which statin to choose and which starting dose to use needs to be individualized on the basis of the patient’s immunosuppressant regimen, potential interactions between statins and other concurrent medications, the presence of comorbid conditions that may alter the risk of statin toxicity, and the patient’s prior experience with statin therapy. Recommendations are summarized in Table 2. It is preferable to start statin therapy at low doses because initiation of treatment at the recommended dose threshold may cause toxicity in some patients. Close monitoring is indicated during statin treatment. Patients also need to be instructed about the importance of reporting potential symptoms of toxicity, such as myalgias, weakness, fatigue, and nausea. If the patient is unable to achieve adequate lipid lowering in response to statin monotherapy, adjunctive treatment with ezetimibe, bile acid sequestrants, niacin, and possibly proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) monoclonal antibody therapy (in patients with CAD or familial hypercholesterolemia) can be considered, but the safety of these drugs in SOT patients is not well characterized. Some of these medications may also negatively impact blood levels of immunosuppressant drugs, such as the reduction in cyclosporine levels in patients treated with bile acid sequestrants.24

Summary

Dyslipidemia is a common comorbidity in SOT patients that is exacerbated by immunosuppressive therapy and results in significant cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. Management of dyslipidemia in SOT patients poses significant challenges as a consequence of the potential for complex drug interactions, as well as limited safety and efficacy data to guide treatment decisions. Statin therapy is safe and efficacious in most patients as long as the treatment is individualized to the patient’s circumstances, recommended statin dosing limits are observed, and patients are closely monitored for development of myotoxicity and/or hepatotoxicity.

Disclosure statement: Dr. Warden has no disclosures to report. Dr. Duell has received honorarium from Akcea, Amgen, Esperion, Kastle, Regeneron, Regenxbio, and Sanofi as well an institutional grant from Retrophin.

References available here.

.jpg)

.png)