S.W. is a 46-year-old male who presented to my office to establish a patient-physician relationship. He had moved to my area six months ago and was running low on his prescription medication. Approximately one year ago, he had developed chest pain consistent with angina and underwent a treadmill stress test was both subjectively and objectively positive, with 2mm ST depression in his anterior precordial leads. He underwent coronary angiography that demonstrated a 90 percent mid-left anterior descending (LAD) stenosis, which was successfully stented with a drugeluting stent, according to his records. In addition, the angiogram demonstrated 30 percent stenoses of his right coronary artery and his mid-circumflex obtuse marginal branch. His medications included atorvastatin 40 mg, ASA 81 mg, Clopidogrel 75 mg, and metoprolol succinate 25mg daily. He became completely asymptomatic and, on his own, he reduced his atorvastatin dose to onehalf tablet daily, because he was under the impression that his remaining disease was “mild.” Laboratory studies at the time of his angiogram revealed the following:

Total cholesterol: 299 mg/dL

Triglycerides: 200 mg/dL

High-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol:

39 mg/dL

Low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol:

220 mg/dL

Fasting glucose: 93 mg/dL

He has never smoked cigarettes. He denies a history of autoimmune disease or kidney disease. His father died suddenly at age 46, but no other information was available. His mother is 75 years old and healthy. He has two daughters, who have not had their cholesterol tested. He has one healthy younger brother who has two children.

His physical examination reveals a blood pressure of 130/86. Waist circumference is 41 inches. The remainder of his physical examination is otherwise unremarkable. Laboratory studies on his current medications reveal:

Total cholesterol: 220 mg/dL

Triglycerides: 160 mg/dL

HDL cholesterol: 38 mg/dL

LDL cholesterol: 150 mg/dL

Shortly after returning to my office to discuss his lab work, S.W. developed atypical chest pain not necessarily related to exertion. Based on his history, a cardiology consultation was requested.

Dr. Rob Greenfield:

When I interviewed and examined this patient, he claimed to be asymptomatic, having had no chest discomfort during the past week. Clearly he needed a “functional study” to exclude coronary ischemia, because he was a patient with prior revascularization (coronary bypass or coronary angioplasty). In this case, I felt that an imaging component should be included in the stress test evaluation to help localize ischemia, if present. In general, a nuclear stress test is more sensitive and more specific than stress echocardiography.* We did not want to miss a “culprit” lesion, so we chose a nuclear stress test. To “rule out” disease in low-risk patients with a low index of suspicion and to avoid unnecessary radiation exposure I would have chosen a stress echo.

His maximal stress cardiolite was negative for ischemia or prior infarct and normal perfusion was displayed. This suggested that his stent had remained patent and that his so-called “non-flow-limiting” disease in his right coronary and circumflex vessels had remained “non-critical.”

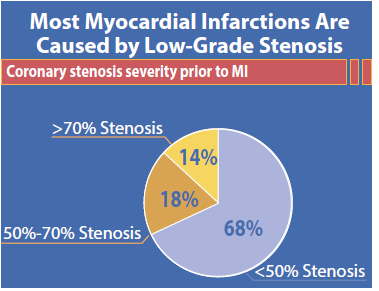

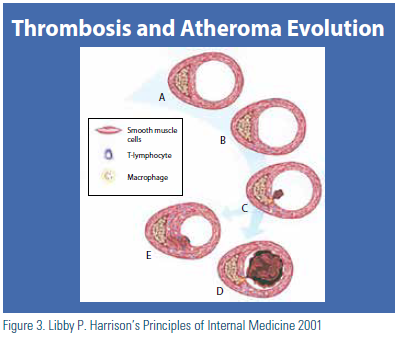

Despite the negative stress test, I explained to the patient that there is no coronary lesion that should be considered “mild.” The literature well documents that most myocardial infarctions are caused by plaques that are less than 50 percent in their luminal stenosis. (Figure 1) Many of these plaques are underestimated by angiography. This has been well demonstrated by intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) in which large intramural plaques that do not compromise luminal diameter can be detected by IVUS but not by angiography. (Figure 2) These plaques usually have large lipid cores in the walls of the coronaries; they are more subject to plaque rupture and subsequent thrombotic occlusion. (Figure 3)

It is important to remember that atherosclerosis is an inflammatory disease fueled by atherogenic lipoproteins. Assessing coronary disease merely by a two-dimension coronary angiogram may underestimate the extent of disease. Most of a patient’s plaque burden lies within the wall of the artery. What we actually appreciate by angiograph is merely the tip of the iceberg and we obtain merely a “lumen-o-gram.”

Glagov showed many years ago that as coronary arteries develop increasing plaque burden, they expand and become larger. This is a process known as “positive remodeling.”1 Angiography to assess this can be quite misleading, because the lumen remains well preserved until the disease is far advanced. Our patient’s 30 percent luminal stenoses may actually misrepresent unstable plaques. Large lipid cores in the walls of the coronary artery are not detected by cardiac catheterization and may require stabilization by aggressive lipid-lowering therapy.

For all of the above reasons, I concurred with Dr. Bottenberg that aggressive lipid therapy was necessary to “delipidate” the patient’s plaques in order to slow progression of his disease and possibly to effect plaque regression.

Dr. Bottenberg:

S.W.’s case represents a fairly typical of patients I see in my office. It is not unusual for a patient to develop a false sense of security when he hears another physician say the words “mild disease” or “noncritical stenosis.” To support the information he received from Dr. Greenfield, I spend a great deal of time explaining atherosclerosis, its progression, and how plaque rupture can leads to events. It is vital that the patient understands his disease process to fully participate in treatment.

He received a 32-percent reduction in his LDL cholesterol on atorvastatin 20 mg daily. I increased his atorvastatin to 40 mg daily. I used the “Rule of Six” (doubling the dose of a statin usually only produces approximately an additional 6 percent LDL-C reduction).2 I suspected that this alone would not allow him to achieve either a target LDL of less than 100 mg/dL (non-HDL < 130) or a total LDL reduction of 50 percent. Therefore, I asked him to add ezetimibe 10 mg daily. Alternatively, I may ask him to try to increase his atorvastatin to 80 mg daily, pending his tolerance of the 40 mg dose. Achieving an optional target of less than 70 mg/dL and non-HDL cholesterol < 100mg/dL may require adding a third agent. In this regard, I may consider a bile acid resin or niacin.

He meets criteria for having the metabolic syndrome: large waist circumference, pre-hypertension, elevated triglycerides, and low HDL. With established disease, this may place him in a “very high-risk category,” underscoring the need for very aggressive lipid-lowering therapy. In addition, he is scheduled to see our staff dietitian. We typically calculate a patient’s protein and calorie requirements and ask the patient to divide them evenly throughout the day. We recommend modest exercise. I anticipate repeating his lab work in six to eight weeks.

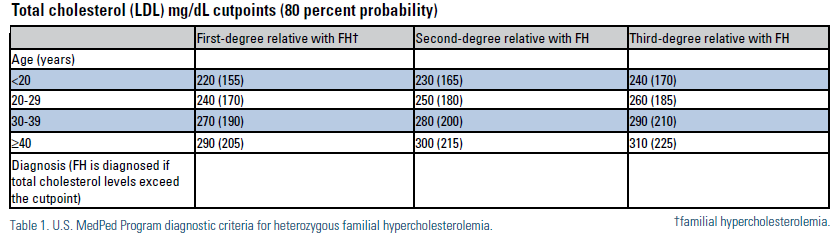

His very high LDL cholesterol and the sudden death of his father at age 46 raises the possibility that he may have heterozygous familial hyperlipidemia.3 Cascade screening is appropriate. We discussed this with the patient and had him ask his daughters to obtain cholesterol screenings. We have asked him to have his brother’s cholesterol tested, as well as his brother’s two children. We typically use the MedPed criteria for the diagnosis of familial hyperlipidemia (FH). (Table 1)

Drs. Greenfield and Bottenberg:

In high risk patients with coronary disease and dyslipidemia, we believe that an aggressive approach is warranted. A close working relationship among the patient, and his physicians can decrease his lifetime risk of future cardiovascular events including stroke, peripheral arterial disease, and acute coronary syndrome. Because of specialized training, National Lipid Association (NLA) members can offer unique skills and perspectives that are likely to improve outcomes.

*There is wide variation amongst published studies for sensitivity and specificity and varies depending on whether there is one, two, or three vessel disease. In general, stress echo may be 70 to 90 percent sensitive and 70 to 80 percent specific and nuclear stress ranges between 85 and 90 percent sensitive and 80 and 90 percent specific. The specificity of stress echo may be somewhat less due to the presence of other forms of structural heart disease such as left ventricular hypertrophy, etc.

Disclosure statement: Dr. Bottenberg has no disclosures to report. Dr. Greenfield has received speaker honorarium from Aegerion and was a principle investigator with Sanofi.

References are listed on page 36 of the PDF.

.jpg)

.png)