I’ve been through many stages with the guidelines. I really think I love them now. Let me tell you why.

I began my internal medicine residency in 1994, and the first time I ever heard that there was such a thing as guidelines, was at residents’ clinic in my first year where I was treating a man following hospitalization for non-cardiac chest pain. I asked my attending to explain how a doctor decides when to use cholesterol medicine. We had results from 4S and WOSCOPS, but statins were not nearly as widely used at that time. I knew they were for high cholesterol, but I didn’t know how high was high enough to prescribe statins. I feel pretty certain that he did not know the answer, but he did know that there were guidelines and suggested I look them up on my own. This was not a strong introduction to guideline directed care or to clinical lipidology.

By the time I finished my residency, I was well trained in the value and rigor of evidence-based medicine (EBM) and knew that there was strong evidence for the use of pravastatin and simvastatin. Since atorvastatin had not completed any major outcomes studies by the time I started my career in primary care in 1997, it was several years before I made this more potent statin part of my regular prescribing. Lower is better was not yet a mantra and I can’t say that the guidelines were burned into my brain entirely.

In 2001, already a budding lipidologist, I attended a lecture at a local hospital that was titled “How not to get sued” or something like that. The lecturer was an MD and a JD, but practicing mostly as an attorney. He made it clear that the best approach when caring for patients is to keep open lines of communication, to be available and honest, and express caring. He also added that there are no absolute “rules” in medicine — except for the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Guidelines. He taught us that every individual needs to be addressed individually, and algorithms should never take the place of clinical judgment. However, he also made it clear to the audience that the evidence supporting the NCEP Guidelines was so strong that clinicians need to have very good reasons if they choose to not follow them. This was the era of medicine just before the propagation of numerous other guidelines in other fields of medicine.

So, in that short period of time, I went from a vague sense that there were guidelines, to they are the “law of the land.”

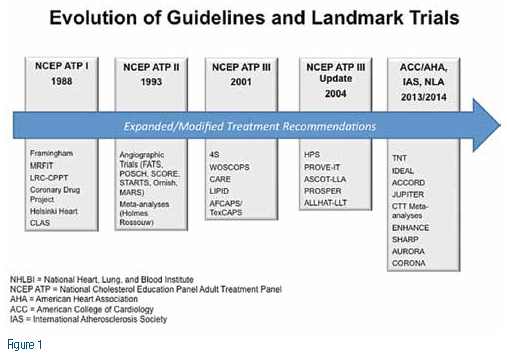

From 2001 (ATP3) to 2013 (American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Guidelines), I think we all got used to incorporating guidelines into our regular practice. EBM was alive and well. The ATP3 had gotten an early makeover in 2004, but it was long overdue for an update. And I had matured into my new role as a clinical lipidologist.

Budgetary changes and the Institute of Medicine (IOM) mandate changed the process of writing guidelines a bit. The IOM approach meant to maximize strength of recommendations. Under the ACC/AHA banner now, the National Guidelines were based exclusively on outcome based randomized placebo controlled clinical trials (RPCTs) and meta-analyses of the same. But our colleagues on the Guidelines Committee stated very clearly that RPCTs do not answer every clinical question and clinicians should think of this as the foundation of care or the minimum standard. Ultimately, the clinician must use all of the science and improvise strategy that works for the patient, while the guidelines remain the default starting point for the discussion with the patient. In other words, consult your local lipidologist for guidance.

The foundation of recommendations based on RPCTs and meta-analyses coupled with the suggested flexibility in the patient- clinician encounter were somehow lost in the discussion to follow these last two years. Why did this message get lost? How is it that clinicians concluded that there was no evidence for non-statins? Or evidence for LDL-C monitoring? Or standards for judging LDL-C response? I don’t think it was the message. I think it was the messaging. At some point, it’s not enough to just be right, it’s critical to promote the value of the message.

Clinicians are busy. We need simple advice for most things. The ACC/AHA Committee composed an elegant focused guideline, suggested that the patient- clinician relationship and decision making is paramount, and then let others dictate the message. For many, it seemed like there were guidelines, but no guidance. In this issue of LipidSpin, we hope you find both.

.jpg)

.png)