Introduction

Patients diagnosed with serious mental illness prescribed antipsychotic medications present unique challenges to healthcare providers. The use of second- generation, or atypical, antipsychotics is associated with significant adverse metabolic effects. These include weight gain, glucose intolerance, and dyslipidemia. Furthermore, cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of death among patients on antipsychotic therapy.1-5 Patients are 1.5 to 3 times more likely to suffer a cardiovascular event such as myocardial infarction or stroke when prescribed medications.3 The monitoring and management of these adverse metabolic effects should be a focal point for healthcare professionals managing patients receiving these medications.

Access to psychiatric care often is limited, in part because of the shortage of psychiatrists and the high cost of specialist care for under-insured and uninsured patients.6 As a result, the responsibility of medication management often falls to the primary care provider, who may not have adequate knowledge of the metabolic effects associated with antipsychotics.7 Considering primary care providers manage 31 percent of patients with severe mental illness,7 it is essential for these clinicians to assist in ensuring that patients who are taking antipsychotics receive the appropriate monitoring to identify any adverse effects early. Primary care providers routinely screen and treat patients with lipid disorders and research shows they can be more effective than psychiatrists at screening and treating patients receiving antipsychotic therapy when they are the prescribers.1 Providers must be alert for patient populations at increased risk, such as the elderly and socioeconomically disadvantaged, because these groups have a higher death rate when taking antipsychotics.1,2,6

Both first- (typical) and second-generation (atypical) antipsychotic drugs induce lipid abnormalities, albeit more so with second- generation agents. The most commonly observed abnormality is an increase of 20 to 50 percent in triglycerides (TG), which is unsurprising given these drugs also are associated with weight gain and elevated glucose levels. A decrease in high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) and increase in total cholesterol (TC) and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) also have been observed, but these lipoprotein changes tend to be minor in comparison to the increases in TG.8

There are several proposed mechanisms that may explain how antipsychotics increase TG levels, including enhanced TG metabolism by stimulating hepatic production or inhibiting lipoprotein lipase-mediated TG hydrolysis, or indirectly via weight gain and obesity.9 The weight gain observed in patients receiving antipsychotics is primarily driven by appetite stimulation due to the effects these medications have on important serotonergic, dopaminergic, and histmaminergic neurotransmitters. Additionally, the sterol-regulatory element- binding proteins (SREBPs), which affect lipid biosynthesis, also plays a major role in increasing TG.8 SREBP-1 regulates fatty acid and TG metabolism, while SREBP-2 regulates cholesterol metabolism. Antipsychotics increase SREBP activity, which may explain the observed increases in TG and cholesterol levels.

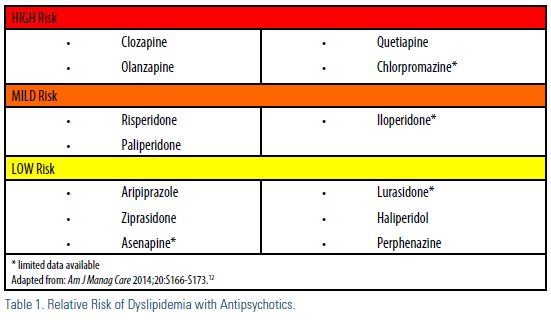

While dyslipidemia appears to be a “class effect,” it is important to note there are key differences regarding the significance of dyslipidemia observed with antipsychotics (Table 1). The Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) trial10 compared the effectiveness and safety of olanzapine, perphenazine, quetiapine, risperidone, and ziprasidone. During the 18-month study, olanzapine was associated with more weight gain and greater increases in blood glucose and lipids compared to the other medications. Olanzapine and clozapine are considered to have the highest risk of metabolic adverse effects, but there is limited data on the metabolic impact of this class of medicine. Despite that, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) required all atypical antipsychotics to carry a warning about the metabolic risks associated with this class of agents.11 As such, monitoring is recommended.

Guidelines for Surveillance and Testing

In 2003, the American Diabetes Association (ADA), American Psychiatric Association (APA), American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE), and North American Association for the Study of Obesity developed consensus guidelines on monitoring and treating patients who are prescribed antipsychotics.13 Research indicates that, despite these guidelines and the known adverse metabolic effects of antipsychotics, adherence to surveillance guidelines is suboptimal.1,5,14 In a three-state study of 109,451 Medicaid patients, despite the published warnings of the FDA, less than 12 percent of the patients undergo lipid testing.6 An updated consensus recommendation has not been formally published since 2003. However, there have been updates to the recommendations based on current research and surveillance. Table 2 contains the current monitoring recommendations.1,5 While these are the minimal recommendations for adult patients, more frequent monitoring may be indicated in pediatric and high-risk populations.4,5 ASCVD risk assessment tools could underestimate the risk of ASCVD in these patients.1 Decisions regarding testing and treatment should include history, cardiovascular risk factors, and the antipsychotic medication prescribed.1 Clinical trials assessing

coordination of metabolic monitoring and treatment between psychiatry and primary care have not been identified.

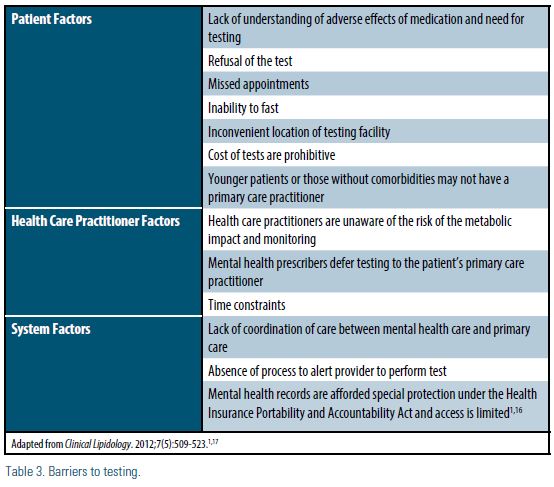

The psychiatric comorbidities of patients taking antipsychotics may make them less likely to take advantage of screening and preventive medical care in comparison with the general patient population, presenting a major barrier to identifying and treating lipid abnormalities.14 Additionally, there is limited research into the barriers of lipid profile screening in patients with serious mental illnesses. Contributing factors to testing barriers may stem from the patient, the provider, and/or system factors (Table 3).1,15 Prescribers of antipsychotics should evaluate barriers specific to their patients and practices.

Conclusions

In recent years, ASCVD-related mortality has declined, in part because of collaboration between organizations that have developed guidelines to improve surveillance and treatment of patients at risk of ASCVD. However, cardiovascular events in patients receiving antipsychotics remain high. Recognizing at-risk patients is essential for appropriate treatment and to improve the quality of life in this population. It seems feasible that ASCVD risk among patients receiving antipsychotics could be reduced with proper screening and management, especially in the primary care setting. The patient would benefit from education on the metabolic effects of antipsychotics and early adoption of lifestyle modifications to reduce their ASCVD. Systems and quality initiatives should be implemented to improve monitoring and treatment.1 Future quality initiatives suggested by the authors include convening a task force to update the consensus recommendations, reviewing the most current research, and designing a method to improve clinicians’ access and adherence to the findings of the panel.

Disclosure statement: Dr. Croy has no disclosures to report. Dr. Dixon has received honoraria from Novartis and Sanofi. Lindsey Kennedy has no disclosures to report.

References are listed on page 31.

.jpg)

.png)