The Very High ASCVD Risk Category

Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk assessment has long been simplified to only several major risk factors and only a few categories, ranging from low to very high, despite the spectrum and magnitudes of risk factors and striking cumulative effects.1 The intensity of treatment is patient risk dependent; higher absolute risk dictates more aggressive treatment.2–7 The very-high risk category evolved to include not only patients with established coronary heart disease (CHD), at risk for having recurrent CHD events,2,3 but also patients with other conditions that carry an absolute risk equivalent for developing new CHD.4 Thus, persons who met CHD risk equivalent criteria had a 10-year risk >20 percent using the risk engine described by the Adult Treatment Panel III Framingham Risk Score (FRS) for hard coronary heart disease (myocardial infarction [MI] + CHD death). CHD risk equivalents include individuals with other forms, or beds, of clinical atherosclerosis, and selected examples were reviewed:4 the one-year rates of major coronary events ranged 2.0 to 3.8 percent and total mortality of 2.9 percent, in studies of patients with peripheral artery disease, 1.9 percent CHD mortality in patients with extensive carotid artery disease, and 1.9 percent CHD mortality in patients that required abdominal aortic aneurysm repair.

Type 2 Diabetes with Multiple Risks Are at Very High ASCVD Risk (CHD Risk Equivalency)

In addition, diabetes mellitus (DM), particularly type 2 diabetes, constitutes a CHD risk equivalent,4 explained by its associated multiple risks; the combination of hyperglycemia plus dyslipidemia and nonlipid risk factors of the insulin resistance (metabolic) syndrome. Several studies reviewed4 indicated one-year rates of CHD >2.0 to 2.5 percent, even among newly diagnosed obese T2DM subjects in UKPDS, but not leaner, where oneyear rates were just under 2.0 percent. It was also recognized that recent-onset type 1 diabetes need not necessarily be designated a CHD risk equivalent. The Finnish East-West study,8 among many studies,4,9 provided the rationale for treating CV risk factors of patients with DM without prior MI, as aggressively as patients with prior MI without DM. Though not all studies have demonstrated every diabetes cohort to possess CHD risk equivalency, with some falling short, (see most recent extensive review,10) exposure to multiple risk factors, i.e. metabo

Patients with ASCVD and Type 2 Diabetes Are at Extreme Risk for Subsequent Events

Regardless of the demonstration of CHD risk equivalency, comparative population studies, show that patient cohorts with DM and prior MI (ASCVD + DM) have 50 to 100 percent higher subsequent ASCVD events or hazard rate compared to those patients with a prior MI without diabetes (ASCVD – DM). In the Finnish East-West study,8 the seven-year incidence of MI was 18.8 percent among patients with a prior MI, but no DM, but 45 percent among patients with a prior MI and DM, and the impact of clinical ASCVD + DM versus clinical ASCVD – DM is consistent.11,16–22 Yet, despite the greater risk for patients with DM and prior CAD, in many studies, guidelines to-date have categorized these two cohorts at the identical very high risk level with identical targeted LDL-C goals. Without doubt, all very-high-risk groups deserve to be managed to the most aggressively targeted LDL-C goal, with cardiovascular prevention as ultimate priority. However, relative to patients with ASCVD without DM, one could argue that a cohort with ASCVD + DM, as an example of extreme risk, may need to be treated to an even lower LDL-C goal, if there is evidence for benefit from an even lower is even better targeted atherogenic cholesterol level. A major problematic issue with targeting LDL-C, may be its deceptively lower level in states of insulin resistance, owing to its discordanceassociated presence of more ominously increased atherogenic remnants and particle numbers23 assessed either as LDL-P or Apo B or the preferred oversimplified surrogate primary target, non-HDL-C, in such states.24 If unable to adopt the more sophisticated measures, the discordance phenomenon may make it imperative that a lower LDL-C goal be chosen for patients possessed of discordance.

Partitioning the Very High Risk by Adding an Extreme Risk Category; Not Just for Diabetes

Thus, clinical ASCVD (i.e. prior MI, TIA, stroke, PAD) or CHD risk equivalent (i.e. diabetes + ≥2 major risks, or CKD) meet criteria for very high risk; i.e. a 10-year risk for MI or CHD death >20 percent (a one-year risk >2 percent) and, to date, has included individuals with one, or more (emphasis added) clinical ASCVD morbidities,6,24 and its management is particularly challenging, requiring a multifactorial approach.25

In addition to DM + ASCVD, several other settings could be considered for meeting criteria for the extreme risk category; where a 10-year risk for MI or CHD death >30 percent (one-year risk >3 percent), and is differentiated from the very high risk that is arbitrarily limited to 10-year risk>20-30 percent (one-year risk 2-3 percent). An acute coronary syndrome (ACS) is associated with significant recurrent ASCVD events; particularly while hospitalized, just post-ACS, and within 30 days; and this risk may persist, though attenuated over the ensuing month(s) and year(s).16,21,26–30 Patients with recurrent events, already at the very high risk targeted atherogenic cholesterol goal (i.e. LDL-C <70 mg/dL), despite treatment with a statin, may remain at extreme risk, by example, in the PROVE-IT29 the twoyear death or MI rate was 16 percent in the pravastatin group and 12.9 percent in the atorvastatin group. Patients with multimorbidities also meet criteria for extreme risk and include a history of clinical ASCVD plus additional morbidity; clinical ASCVD + CKD;31 multiple ASCVD beds;13,21,28,32,33 Familial Hypercholesterolemia (FH) + ≥1 bed(s) of ASCVD, especially ACS with FH.34

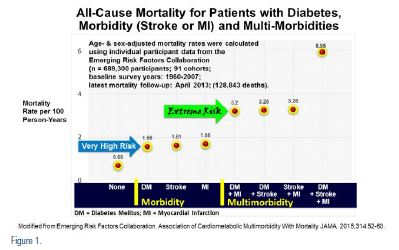

The Emerging Risk Factor Collaboration analysis13 (see Figure 1) evaluated all-cause mortality among 689,300 participants in 91 cohorts and re-established DM as an ASCVD risk equivalent, with the same mortality as those cohorts with an MI, or a stroke, without diabetes, and a 100 percent increased mortality with dual morbidities (MI + DM, stroke + DM, or MI + stroke) and a 200 percent increased mortality with all three, DM + MI + stroke. Clearly, the very high risk morbidities were associated with 6–8 years of life lost, while extreme risk dual morbidities were associated with 12–16 years of life lost.

The Targeted LDL-C Goal in 2004 Was Lowered for Very High Risk Patients to <70 mg/dL

The NCEP ATP III 2004 Update concluded that a targeted LDL-C goal of <70 mg/dL was optional for very-high-risk patients36 based on new clinical trial data including PROVE-IT35 and the sub-group and subset analyses of Heart Protection Study-HPS,37 and the intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) trial, REVERSAL.38 The AHA/ACC 2006 Update concluded, based on additional studies, that a targeted LDL-C goal of <70 mg/dL was reasonable for very high risk patients, i.e. secondary prevention.39 Despite controversy,40,41 multiple national and international guidelines support recommendations targeting LDL-C treatment goals to <70 mg/dL for very high risk individuals.6,7,24,36,39,42-49

Accumulating Evidence for Even Lower Is Even Better for Targeted LDL-C

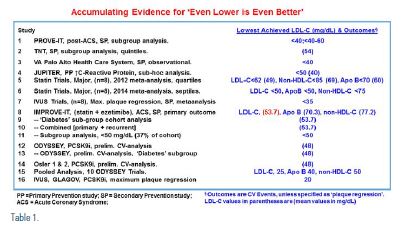

Over the last decade, evidence has been accumulating that support targeting LDL-C to even lower levels in all ASCVD risk categories. Given the unacceptably high residual risk, noted in most randomized clinical trials, even in the settings of high intensity monotherapy statins, the rationale for an even lower is even better goal may be viewed as imperative. Substantial undertreatment of high-risk patients could result from the inadvertent utilization of current guidelines, especially if a lower LDL-C will indeed reduce ASCVD events. In each of the following studies or analyses, the lowest hazard ratio for CV disease burden or events was reached with lower levels for the markers of atherogenic cholesterol (i.e. for LDL-C far lower than just under <70 mg/dL) (see Table 1). Such a therapeutic strategy would be extended to patients at very high or extreme risk who already have a baseline LDL-C minimally <70 mg/dL.

A sub-group analysis of the 2005 PROVE-IT study50 found ACS individuals achieving very low LDL levels <40 mg/dl and 40 to 60 mg/dl groups had fewer major CV events. A sub-group post-hoc analysis of the 2005 TNT trial, of more stable CHD patients, demonstrated that those achieving very low LDL-C51 in the lowest quintile defined as LDL-C level <64 mg/ dl (mean LDL-C 54 mg/dL) had the fewest events. An observational 2007 VA Palo Alto Health Care System study52 demonstrated improved survival among patients placed on statins despite pre-treatment LDL levels <40 mg/dL. In the 2011 subgroup/posthoc analysis of the primary prevention JUPITER trial,53 among individuals with risk based on a hsCRP > 2mg/dL and metabolic syndrome (~45 percent) achieving LDL-C levels <50 mg/dL (median 44 mg/dL) vs. not <50 mg/dL (median 69 mg/dL) had the lowest MACE rate.

A meta-analysis of eight major statin trials (n=38,153 patients), divided into quartiles of achieved LDL-C,54 the lowest CV event rate occurred in those in the lowest quartile of LDL-C <62 (mean 49mg/dL), non-HDL-C <85 mg/dL (mean 69 mg/dL), and Apo B <70 mg/dL (mean 60 mg/dL). In a second meta-analysis of the same eight statin trials, divided into septiles, to evaluate even lower LDL-C levels achieved;55 showed that patients with LDL-C <50 mg/dL, Apo B <50 mg/ dL, or non-HDL-C <75 mg/dL have the lowest MACE rate. In a 2014 analysis of eight intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) studies,56 a continuous relation between changes in plaque volume versus achieved LDL-C; those achieving LDL-C levels 15 to 30 mg/dL (mean 26 mg/ dL) achieved progressively more regression of total plaque volume.

In the IMPROVE-IT study,57 in ACS patients, from a baseline LDL-C of 95 mg/ dL, at a mean six-year follow-up, the group allocated simvastatin 40 mg plus placebo achieved an LDL-C 69.5 mg/dL vs. 53.7 mg/dL for the group allocated simvastatin 40 mg plus ezetimibe 10 mg, or a 16.7 mg/ dL between-group difference. The primary composite ASCVD end-point showed a 2 percent between-group absolute risk reduction or a 6.4 percent relative risk reduction (RRR) in (p=0.016), for a number needed to treat (NNT) of 50. In the secondary (MACE: CV death, nonfatal MI or non-fatal stroke) outcome 22.2 percent events occurred in the simvastatin plus placebo group and 20.4 percent events in ezetimibe plus simvastatin group for a 1.8 percent between-group absolute risk reduction or a 10.0 percent RRR (p=0.003) and the NNT was 56. In the pre-specified major diabetes subgroup,57,58 27 percent of the entire cohort, patients with diabetes allocated simvastatin plus placebo had the highest primary endpoint (45.5 percent) event rate, but the most significant primary event lowering (40.0 percent) in those allocated ezetimibesimvastatin, for an absolute risk reduction (ARR) of 5.5 percent and a 12.1 percent relative risk reduction (RRR) and the NNT was 18. The analysis of 4,131 additional, or recurrent events that occurred over the entire seven years,59 demonstrated a 12 percent RRR noted in these additional or recurrent events (p = 0.007), for a 9 percent RRR in total events=primary + recurrent events (p = 0.007), and the NNT was 23. In another IMPROVE-IT subgroup analysis,60 a distribution curve was generated of all patients by LDL-C at one month. The median LDL-C was 56 mg/ dL; with the following distributions <30 mg/dL, n=969 (6 percent); 30-49 mg/dL, n=4755 (31 percent); 50-69, n=5482 (36 percent); >70 mg/dL, n=3989 (26 percent), and 5,724 participants (37 percent) were found to achieve an LDL-C <50 mg/dL. This analysis demonstrated that targeting LDL-C to a goal <50 mg/dL (<1.3 mmol/L) further reduces CV Risk [adjusted HR: 0.90 (95 percent CL 0.85- 0.96), p = 0.002].

In 2015, preliminary pooled post-hoc analyses from studies with proprotein convertase subtilisin kexin 9 (PCSK9) inhibitors evolocumab61 after 52 weeks and alirocumab62 after 78 weeks showed in both analyses, the mean baseline LDL-C was approximately 120 mg/dL and the mean LDL-C achieved was 48 mg/dL, and although not long term outcome trials, demonstrated a promising ~50 percent RRR in CV events. Pooled Analysis of 10 ODYSSEY Trials63 reached levels of LDL-C, 25 mg/dL, ApoB 40 mg/dL, non-HDL-C 50 mg/dL further support these findings.

The IVUS trial, GLAGOV,64 utilizing the PCSK9 inhibitor, evolocumab, demonstrated regression of plaque volume with maximum plaque regression reached at an LDL-C of 20 mg/dL.

Thus, there is accumulating evidence that LDL-C levels below 55 mg/dL are associated with even lower ASCVD outcomes, either assessed as regression by IVUS, or reduced clinical events.

The American Diabetes Association, in its 2016 updated lipid guidelines,65 included ASCVD major risk factors as LDL-C >100 mg/dL (2.6 mmol/L), high blood pressure, smoking, overweight and obesity, and family history of premature ASCVD. In ACS patients with diabetes who have LDL-C levels ≥50 mg/dL (1.3 mmol/L) or in patients with a history of ASCVD who cannot tolerate high-dose statin, the 2016 ADA recommendations are for ezetimibe to be added to moderate dose statin.

The American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists/American College of Endocrinology (AACE/ACE) recognizing the imperative, introduced, adopted, and incorporated the concept of partitioning the very-high-risk category to include an extreme risk category in their 2017 guidelines for management of dyslipidemia and prevention of atherosclerosis66 and their 2017 AACE comprehensive type 2 diabetes management algorithm. The extreme risk category currently includes patients with progressive ASCVD, that may be defined by recurrent events, multiple beds of ASCVD, or patients with single bed ASCVD, who also have DM and/or stage 3 or 4 CKD and/or FH, as well as patients with premature ASCVD (age a male <55 years or female <65 years). While for the very-high-risk persons, the suggested LDL-C goal is <70 mg/dL, for the extreme risk, AACE recommends an LDL-C goal of <55 mg/dL, despite an LDL-C <70 mg/dL, as a reasonable clinical strategy, based on currently available data and the evidence-based IMPROVE-IT clinical trial.

Summary

In summary, there is compelling data in support of an extreme risk category and, also accumulating evidence for benefits derived from a philosophy of targeting atherogenic cholesterol to even lower is even better goals. Refinements in this extreme risk category definition is in a dynamic mode, to be continuously updated as a better understanding of, not only the impact of ASCVD multi-morbidities, but also the role of atherosclerosis imaging studies, such as coronary artery calcification, exaggerated major risks, nontraditional risks, such as lipoprotein(a), and co-morbidities, is explored. Furthermore, the goals of targeted atherogenic cholesterol particle lowering for the extreme risk individual may be expected to evolve with the results of pending and future clinical trials, with newer more potent LDL-C lowering agents, even among extreme risk populations, such as patients with stage 5 CKD on hemodialysis and CHF, where achieving current goals of lipid therapy have been unsuccessful in reducing risk.

Proceeding forward, the very-high-risk category is maintained, but defined more precisely as the presence of an established single, stable ASCVD morbidity, including patients with recent, but beyond three months of hospitalization for their first ACS and, also patients without a prior ASCVD event, but considered ASCVD risk equivalents, such as patients with multiple risks and diabetes or CKD ≥3, or patients with FH. Recognizing that multiple other ASCVD risk engines exist globally, utilizing, as an example,

Based on epidemiological studies and clinical trials, the extreme risk category would be defined as a 10-year risk of ASCVD risk estimated at >30 percent (one-year risk >3 percent) and applicable patients are found in the setting of immediate hospitalization for ACS or presence of ASCVD multi-morbidities (see Figure 2). Currently, evidence-based IMPROVE-IT suggests a targeted LDL-C goal <55 mg/dL for the extreme risk category, but surrogate imaging (IVUS) outcome studies, subgroup analyses and meta-analyses of IVUS, and clinical trials, as well as preliminary results utilizing PCSK9 inhibitors demonstrate lower clinical outcomes and, therefore suggest the same lower atherogenic cholesterol goals for the very-high-risk category. Therefore, while targeting an LDL-C <55 mg/dL, appears appropriate for both very high and extreme categories, even more intensive therapy may be warranted for individuals at extreme risk.

Disclosure statement: Dr. Rosenblit has received speaker honoraria from Astra Zeneca (Bristol Myers Squibb), Boehringer-Ingelheim, GlaxoSmith-Kline, Janssen, Merck, Novo Nordisk, and Takeda; research site clinical trial funds from Amgen, Astra-Zeneca, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, Ionis, Lilly, Lexicon, Merck, Novo Nordisk, Orexigen, and Sanofi-Regeneron; and honoraria for advisory board activities from Amarin, Amgen, Astra-Zeneca, and Ionis-Akcea Therapeutics. Dr. Handelsman has received consulting and speaker honorarium from Amgen, AstraZeneca, and Janssen; he’s received research grants from Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Boehringer- Ingelheim, Esperion, Grifolis, GlaxoSmithKline, Hamni, Intarcia, and Lexicon; he’s received speaker honoraria from Amarin and Boehringer-Ingelheim/Lilly; he’s received consulting honoraria from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Boehringer-Ingelheim, and GlaxoSmithKline.

Article By:

Clinical Professor of Medicine, Division of Endocrinology

UC Irvine, School of Medicine, Irvine, CA

Co-Director, Diabetes Outpatient Clinic

UCI Medical Center, Orange, CA

Private Practice: Director & Principal Investigator

Diabetes / Lipid Management & Research Center

Huntington Beach, CA

Diplomate, American Board of Clinical Lipidology

.jpg)

.png)