Acetylsalicylic acid, or aspirin, has played a central role in the secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease (CVD) for decades, but the data for primary prevention is less clear. The current recommendations are conflicting. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) and the American Heart Association (AHA) recommend consideration of aspirin use in patients who have a >10% risk of CVD in 10 years, while the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has cautioned against the use of aspirin for primary prevention.(1) This has generated significant confusion among clinicians as to the appropriateness of aspirin in primary prevention.(2) Three recently published studies have attempted to shed light on this controversial area with the hope of better defining aspirin’s role in the primary prevention of ASCVD.

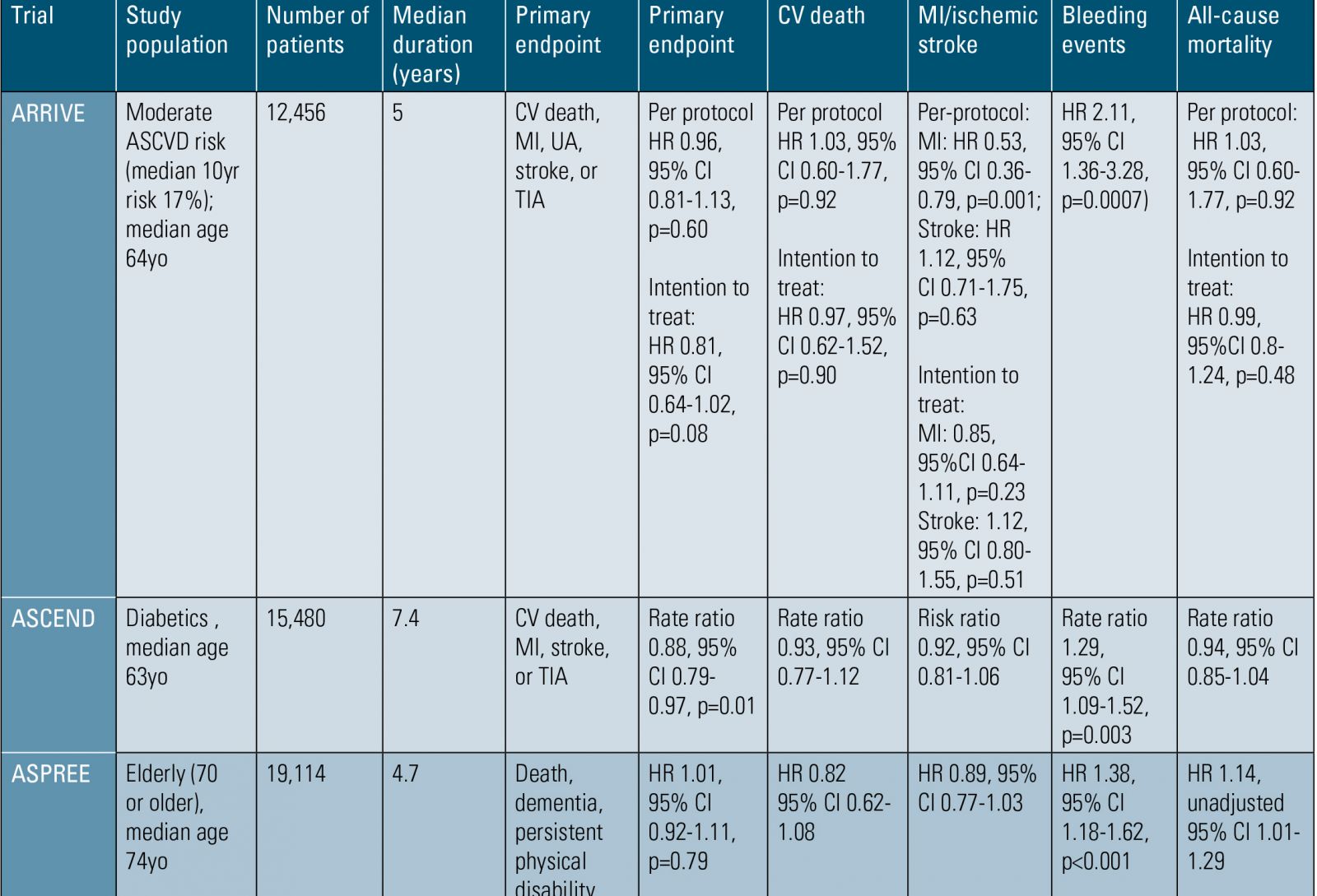

In A Study to Assess the Efficacy and Safety of Enteric-Coated Acetylsalicylic Acid in Patients at Moderate Risk of Cardiovascular Disease (ARRIVE), 12,456 patients with moderate ASCVD risk and no prior history of cardiac events were randomized to 100mg enteric-coated aspirin versus placebo.(3) In the intention-to-treat analysis, there were no significant differences in the primary endpoint of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction (MI), unstable angina, stroke and transient ischemic attack (TIA) between the groups assigned to aspirin versus placebo (4.29% vs 4.48%; HR 0.96, 95% CI 0.81-1.13, p=0.60). However, this trial had a very high medical non-compliance rate of almost 40%, making it difficult to interpret the results. For example, in the per-protocol analysis, aspirin was associated with a 47% relative risk reduction in MI (HR 0.53; 95% CI 0.36-0.79). As with other trials, there was an increased risk of gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding in the aspirin group (0.97%) compared to the placebo group (0.46%; p=0.0001).

In the Effects of Aspirin for Primary Prevention in Persons with Diabetes Mellitus (ASCEND) study, 15,480 diabetics with no prior CVD underwent randomization to 100mg aspirin or placebo daily.(4) During a follow-up of 7.4 years, serious vascular events (MI, stroke, TIA, or death from any vascular cause) occurred in a lower percentage of those in the aspirin group compared to the placebo group (8.5% vs. 9.6%; HR 0.88, 95% CI 0.79-0.97, p=0.01). Bleeding was higher in the aspirin group compared to the placebo group (4.1% vs. 3.2%; HR 1.29, 95% CI 1.09-1.52, p=0.003), with the authors concluding that the modest benefit appeared to be counterbalanced by the increased risk of bleeding.

The ASPREE trial (ASPirin in Reducing Events in the Elderly) evaluated aspirin use in elderly patients.(6) During the study, 19,114 people 70 years of age or older without known ASCVD (≥ 65 years old among U.S. blacks or Hispanics) recruited from Australia and the U.S. were randomized to 100mg aspirin or placebo. At a median follow-up of 4.7 years, the primary endpoint (composite of death, dementia or persistent physical disability) was 21.5 events per 1,000 person-years in the aspirin group versus 21.2 per 1,000 person-years in the placebo group (HR 1.01, 95% CI 0.92-1.11; p=0.79). Death from any cause was 12.7 events per 1,000 person-years in the aspirin group and 11.1 events per 1,000 person-years in the placebo group (HR 1.14, unadjusted 95% CI 1.01-1.29). Additionally, the rate of major hemorrhage was higher in the

ASCVD, atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; yo, years old; CV, cardiovascular; MI, myocardial infarction; UA, unstable angina; TIA, transient ischemic attack; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Table 1. Aspirin in Primary Prevention Outcomes Trials.

“These studies send a strong signal that we must use caution in recommending ASA to patients for the primary prevention of ASCVD.”

14 LipidSpin • Volume 17, Issue 3 • May 2019Official Publication of the National Lipid Association15aspirin group than in the placebo group at 3.8% vs 2.8%, respectively (HR 1.38, 95% CI 1.18-1.62; p<0.001).

These studies send a strong signal that we must use caution in recommending aspirin to patients for the primary prevention of ASCVD. However, there are important caveats to this recommendation, because several of these studies had significant methodical flaws that make it difficult to draw firm conclusions. Secondly, none of these studies examined the highest-risk primary prevention patients. For example, the observed cardiovascular event rate in the ARRIVE trial was 9% instead of the expected 17%, making this a lower risk population. These studies do not exclude the possibility that high-risk (> 20% ASCVD risk in 10 years) primary-prevention patients would have net clinical benefit from aspirin therapy. Furthermore, it is difficult to weigh the relative consequences of a gastrointestinal bleed versus a cardiovascular event. In most of these trials it was assumed that, if the CVD event rate was equal to the non-fatal GI bleeding rate, this indicated a negative trial. Finally, the concept that ASCVD prevention is a dichotomous variable (either primary or secondary), is antiquated and often misleading. A greater focus on improvement in risk-assessment utilizing atherosclerosis imaging and/or biomarkers in addition to clinical risk calculators may be useful in better determining the patients who truly are high risk and, thus, more likely to benefit from aspirin therapy. In light of the current evidence, aspiring should be reserved for high-risk primary prevention after a clinician-patient discussion focused on risks and benefits. In those patients started on aspirin who also are at high risk for bleeding complications, consideration of concomitant proton pump inhibitor therapy to reduce bleeding risk also should be discussed.(6,7)

Disclosure statement: Dr. Sperling has no financial disclosures to report. Dr. Dhindsa has no financial disclosures to report. Dr. Mehta has no financial disclosures to report. Dr. Sandesara has no financial disclosures to report. Dr. Baer has no financial disclosures to report.

.jpg)

.png)