Loretta is a 60-year-old white woman with a past medical history significant for hypercholesterolemia, mitral regurgitation, hypertension, pregnancy-induced hypertension (twice) and a family history of premature coronary heart disease (her father had myocardial infarction at age 53). Recent clinical examination is noted below:

The patient has refused medical therapy for hypertension and does not even want to consider lipid-lowering therapy.

Use of Risk Calculator

This patient’s 10-year ASCVD risk of 5.9% represents “borderline” ASCVD risk. The patient still is refusing medical therapy and has not been successful with lifestyle changes. The aim of this case study is to demonstrate how the 2018 Multisociety Cholesterol Guidelines can inform the evaluation and treatment of cardiovascular disease risk in patients at “borderline” risk.

In the United States, approximately 60% of patients are aware of having high lowdensity lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol. Of that 60% of patients who know, only 70% are being treated.(1) In the recent Heart Disease and Stroke statistics, it was reported that approximately 32% of the ASCVD-free, non-pregnant U.S. population between the ages of 40 and 79 has >10% risk of a first cardiovascular disease event.(2) These numbers highlight the need to risk-stratify the borderline and intermediate risk population to prevent adverse CVD events.

Risk factors included in the ASCVD questionnaire to estimate risk are age, sex, cigarette smoking, blood pressure, serum total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) and diabetes mellitus. Using the pooled cohort equation, 2013 cholesterol guidelines propose a 10-year risk of ASCVD ≥7.5% as a threshold for statin treatment.(4) The 2018 guidelines categorize the 10-year risk for ASCVD as low risk (<5%), borderline risk (5%-7.5%), intermediate risk (7.5% to <20%) and high risk (≥20%).(3)

Risk-Enhancing Factors

Increased Risk in Women and Other Patients with Inflammatory Disease

Recognizing that women can have a unique set of ASCVD risks is a new and important addition to these guidelines. In a population cohort study of 146,748 women with first pregnancy who developed hypertensive disorders during pregnancy, the women were followed for more than 10 years for a cardiovascular disease event. There was a substantially higher rate of ASCVD in hypertensive pregnant women, with a hazard ratio of 2.2.(5) Furthermore, women who develop pregnancy-induced hypertension (PIH) are more likely to develop hypertension later in life. A study of more than 1 million women looking at the incidence of postpregnancy hypertension demonstrated 18 LipidSpin • Volume 17, Issue 4 • August that 1/3 of women with PIH may develop

A meta-analysis of 37 studies showed that patients with metabolic syndrome have an increased risk of cardiovascular events.(10) High-sensitivity c-reactive protein (hsCRP) is another independent risk factor marking the presence of low-grade systemic inflammation. JUPITER (Justification for the Use of Statins in Prevention – an Intervention Trial Evaluating Rosuvastatin) showed that, in healthy people without hypercholesterolemia but with inflammation manifested as elevated hsCRP, rosuvastatin 20mg (high-intensity statin dose) significantly reduced the incidence of major cardiovascular events. (12)

“In the recent Heart Disease and Stroke statistics, it was reported that approximately 32% of the ASCVD-free, non-pregnant U.S. population between the ages of 40 and 79 has >10% risk of a first cardiovascular disease event.”

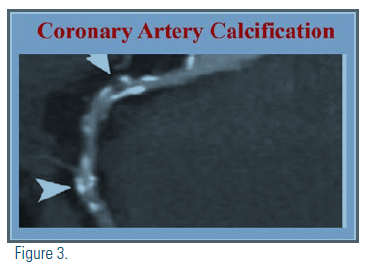

Coronary Calcium Score for Some

If, after a clinician-patient discussion and review of all the risk factors, the decision regarding the use of statins remains uncertain, the guidelines suggest considering using the coronary artery calcium (CAC) score to reclassify the risk. Estimation of CAC remains an independent predictor of cardiovascular events and is used to identify patients who qualify for primary prevention in the intermediate ASCVD risk group. The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) and German Heinz-Nixdorf Recall (Risk Factors, Evaluation of Coronary Calcium, Lifestyle) (HNR) studies had a similar design and goals to assess to what degree CAC predicted CVD events beyond traditional risk factors.(11) The guidelines recommend that, with a CAC of zero, statins are not indicated unless diabetes or other risk factors are present. A CAC score of 1-99 favors statin therapy, especially after age 55. For a CAC score >100, statin therapy is indicated.

Summary

This case illustrates the importance of looking at each patient’s ASCVD profile closely and provides a step-by-step decision-making tree. Clinicians should start by assessing risk using the ACC/AHA pooled-cohort equation risk calculator and move on to a detailed discussion of the patient’s personalized overall risk utilizing his or her unique risk-enhancing features highlighted in the new guidelines. Our patient’s risk of 5.9% is consistent with “borderline risk” but, by utilizing a personalized approach, she has multiple cardiovascular enhancing factors elevating her risk.

The patient was adamantly against any pharmacologic therapy. The guideline recommendation of using the coronary calcium score when risk and treatment still are uncertain is helpful in this case. The patient went on to have a CAC score of 175 Agaston units, elevating her risk and confirming the need for statin therapy.

This case is an example of how to navigate proper assessment and treatment for borderline-risk patients. The patient conversation starts with the PCE risk score and allows the physician to consider other unique clinical variables to reach an appropriate recommendation.

We applaud the inclusion of new risk factors in these guidelines to crystallize a decision pathway to appropriate treatment. This list includes risks unique to women, such as pre-eclampsia and early menopause, which are associated with higher ASCVD mortality. Bringing attention to pre-eclampsia as a cardiovascular risk factor is valuable, because it is not well known amongst physicians. The inclusion that chronic inflammation – either because of chronic disease such as rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, HIV or unknown etiology manifested by elevated hsCRP, as well as chronic kidney disease – contributes to increased cardiac risk also is important.

“This case illustrates the importance of looking at each patient’s ASCVD profile closely and provides a step-bystep decision-making tree.”

This patient had many risk enhancers, including a positive family history of premature CHD, history of pre-eclampsia, metabolic syndrome, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia and elevated hsCRP. These findings significantly elevate the “borderline risk” from the PCE calculator and clearly emphasize the importance of an individualized evaluation, which then makes the recommendation of at least moderate-intensity statin therapy easy.

Loretta’s CAC score was helpful in convincing her of the merits of pharmacotherapy for hypercholesterolemia and hypertension and she was started on high-intensity statin therapy. (See attached image)

Cardiology is moving into an era of precision medicine. All physicians should engage their patients in a discussion to refine the patient’s personalized cardiovascular risk, facilitated by the 2018 guidelines. Patient understanding of risk is essential to complying with lifestyle modification and medical therapy. Patients need to understand why, and these new guidelines give us the how.

Disclosure Statement: Dr. Mintz has received honoraria from Regeneron, Sanofi, Jansen, and ALCEA. Dr. Tummala has no financial disclosures to report.

.jpg)

.png)