Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of death worldwide, accounting for nearly 18 million deaths in 2017 with 859,125 of those occurring in the United States – a number higher than death from all forms of cancer combined.(1) Unfortunately, this global number is anticipated to rise to over 22 million by 2030.

About one third of American adults have some form of CVD, with costs of the management of these conditions surpassing $351 billion between 2014 and 2015.(1)

Statins have been shown to decrease the risk of major vascular events by about 22% per 1.0 mmol/L reduction in LDL cholesterol, with greater risk reductions seen by lowering the LDL-C even further. (2) This risk reduction is also seen in those without a history of CVD or diabetes.(3) However, although their use has increased over time (4), adherence remains low.(5) It is imperative to understand the barriers that lead to patients to not take these medications with high adherence.

In this article we intend to identify and discuss some of the barriers frequently seen in clinical practice as well as a stepwise approach to improve them. For this purpose, we will start with a patient case discussion.

Case Discussion

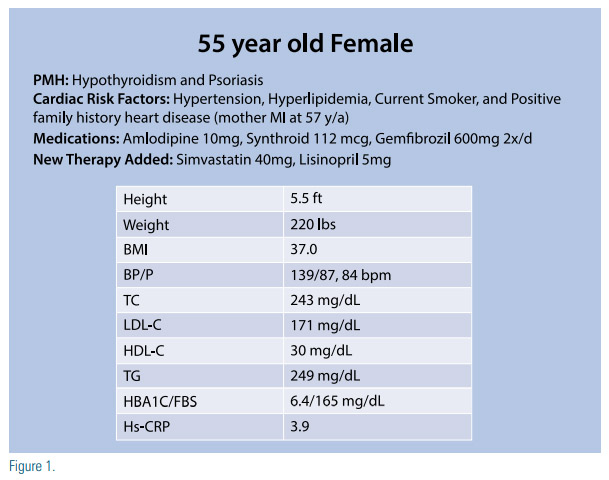

The patient is a 55-year-old Caucasian female with a history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, hypothyroidism, and psoriasis. She is a current smoker and has a family history of premature atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) with her mother having a myocardial infarction at 57 years of age. Her medications and laboratory results are depicted in Figure 1.

Without further discussion she is started on simvastatin 40mg and lisinopril 5mg. On her follow up visit six weeks later, she mentions she developed muscle aches within two weeks of starting the above medications, and decided to stop the simvastatin after her neighbor told her this was likely the culprit of her symptoms. She mentions she does not want to be on statins and wants to work on lowering her cholesterol with diet and exercise.

Her doctor documents her wishes and recommends follow up in six months. By the time of her follow up she no longer had muscle aches, her repeat lipid profile was unchanged from prior, and her doctor recommends starting atorvastatin 10mg. However, she refuses and her doctor, frustrated, instructs her to “go on a diet” and return to clinic in six months.

Some of the questions that this case can raise include:

• What should have been done prior to prescribing statin?

• Does she know her cardiovascular risk?

• Does she understand the importance of statin therapy?

• Why did this patient develop muscle aches?

• What could have been done to prevent this from happening?

• What would help this patient be more receptive to be re-challenged with statins?

As stated in the 2018 AHA/ACC Multisociety Guideline on the Management of Blood Cholesterol, before initiation of therapy, a detailed discussion between the clinician and the patient should take place in order to promote shared decision-making and it should include the potential for ASCVD riskreduction benefit, adverse effects, drugdrug interactions, and patient preferences. This is a class IA recommendation, associated with the highest level of evidence and support.(6) Unfortunately, that was not the case with our patient.

Assessing a Patient’s Cardiovascular Risk

First of all, before prescribing therapy, this patient’s risk for ASCVD should have been calculated using the pooled cohort equation (6) which would have put her at an intermediate risk for ASCVD with 15.9%, 10 years risk for ASCVD. However, this risk assessment should be individualized as this tool, although it is powerful at predicting population risk, does not take under consideration other factors that can further increase a patient’s individual cardiovascular risk. These are known as risk enhancing factors and are illustrated in the 2018 AHA/ACC Multisociety Guideline on the Management of Blood Cholesterol as:

• Family history of premature ASCVD

• Persistent elevated LDL-C ≥160 mg/dL

• Metabolic syndrome

• Chronic kidney disease

• Conditions specific to women (e.g., preeclampsia, premature menopause)

• Chronic inflammatory conditions (especially psoriasis, rheumatoid arthritis, or HIV/AIDS)

• Ethnicity (e.g., South Asian ancestry)

• Persistently elevated triglycerides (≥175 mg/dL)

• In selected individuals biomarkers also need to be considered:

• hs-CRP ≥2.0 mg/L

• Lp(a) levels of >50 mg/dL or >125nmol/L

• apoB ≥130 mg/dL

• Ankle-brachial index <0.9

This information should be presented to the patient in detail during the clinicianpatient risk discussion in order for her to understand the potential benefits of both lifestyle modification and statin therapy. Clinicians need to engage the patient as a partner, and should explain and not dictate, that the higher the risk for ASCVD, the greater the benefit of lipid-lowering therapy. Additionally, adverse effects of statins, potential drug-drug interaction, as well as cost need to be discussed. This patient was able to schedule a dedicated visit with a Lipid Specialist to address this problem so was able to take the time to ask about her hesitancy regarding atorvastatin therapy. It turned out that she was afraid of memory loss, which happened to her elderly father after initiating atorvastatin therapy. A quick call to her father’s neurologist clarified this misunderstanding. Her father had Alzheimer’s disease and had been losing his memory one year before atorvastatin therapy. After taking the time to relay this information to the patient, she was more amenable to statin therapy. Patient engagement remains the foundation for any therapy.

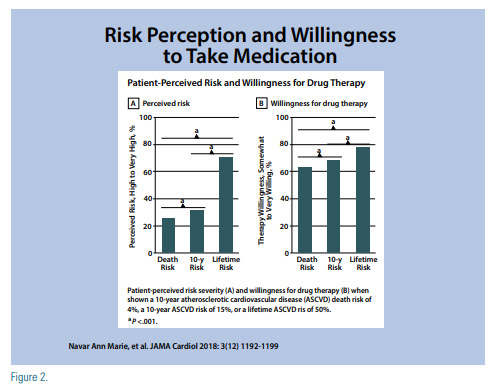

Patient willingness to start therapy can be affected by the way the information is presented. A study evaluated patient’s “perceived risk” and “willingness to take medications” in 3,566 participants of the Patient Provider Assessment of Lipid Management (PALM) Registry when risk was presented as a 15% 10-year ASCVD event risk, a 4% 10-year CVD death risk, and a 50% lifetime ASCVD event risk.(7) This study concluded that patients had higher risk perception and willingness for therapy when shown lifetime risk estimates, than when shown 10-year estimates. Additionally, when risk was presented with a face pictogram where a green happy face represented a positive outcome while a red sad face represented a negative one, the perceived risk and willingness for therapy was lower than when the risk was shown as a bar graph (Figure 2).

Considering this, in order to make the risk communication effective, it has to be considered which risk score is used and how this information is displayed. For our patient who has a 10-year ASCVD risk of 15.9%, her lifetime ASCVD risk is 50%.

In this intermediate risk group, should the decision on whether to start statin therapy remain uncertain to the clinician or to the patient, measuring a coronary artery calcium (CAC) score can be considered.(6) A CAC score of zero suggests low risk and avoiding statin use in these patients can be considered, unless they have diabetes, a family history of premature coronary heart disease, or they are cigarette smokers. When the CAC score is between 1 and 99 the use of statins is favored, especially if older than 55 years, and when the score is ≥100 and/or ≥75th percentile, statins should be initiated.(6)

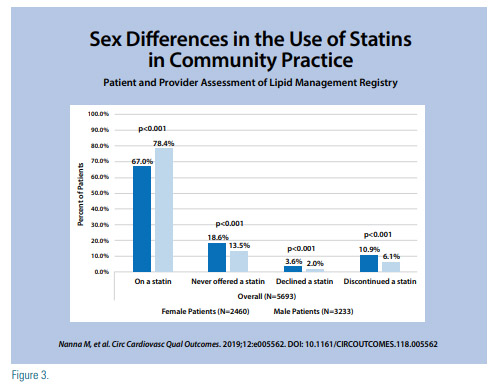

Statins are often underused because of a lack of knowledge of their importance and true side effect profile. A significant gender difference regarding statin use has been identified. Women more than men are less likely to be told about their risk for CVD being related to their LDL-C levels.(8) The reality is that statins are under-prescribed in women,(9) and when they are prescribed, women are less likely to be on higher intensity statin therapy or to achieve their optimal LDL-C goal (10), despite statins therapy being equally beneficial for both women and men at reducing CV events and all-cause mortality (Figure 3).(11)

The poor implementation of guidelinebased therapy can be driven by a clinician’s beliefs regarding statin risks and benefits as it was depicted on a study from the PALM registry, where 774 clinicians completed a survey that assessed their knowledge of the 2013 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Treatment of Blood Cholesterol to Reduce Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Risk in Adults, their belief in statin benefit, and statin safety concerns.(12) The study revealed that guideline knowledge was not associated with a difference in statin use, and patients treated by clinicians who believed in the benefits of statins were more likely to utilize guideline-based therapy, however, those patients treated by clinicians who had concerns about statin safety were less likely to be on guidelinebased statin therapy and to achieve an LDL-C <100 mg/dL.

Regardless of their current risk, a hearthealthy lifestyle should be emphasized in every patient, as this will reduce their risk for ASCVD and for metabolic syndrome.(6) A heart-healthy lifestyle can be achieved by following Life’s Simple 7, which is defined by the American Heart Association as the seven risk factors that can be improved through lifestyle in order to achieve ideal cardiovascular health.(13) These goals and metrics set for adults >20 years are:

1. Current smoking

a. Poor → Yes

b. Intermediate → Former ≤12 mo

c. Ideal → Never or quit >12mo ago

2. BMI, kg/m2

a. Poor → ≥30

b. Intermediate → 25-29.9

c. Ideal → <25

3. Physical activity

a. Poor → None

b. Intermediate → 1–149 min/wk of moderate activity or 1–74 min/wk of vigorous activity or 1–149 min/wk of moderate and vigorous activity

c. Ideal → ≥150 min/wk of moderate activity or ≥75 min/wk of vigorous activity or ≥150 min/wk of moderate and vigorous activity

4. Diet pattern score

a. Poor → 0-1

b. Intermediate → 2-3

c. Ideal → 4-5

5. Total cholesterol, mg/dL

a. Poor → ≥240

b. Intermediate → 200-239 or treated to goal

c. Ideal → <200

6. Blood pressure, mmHg

a. Poor → SBP ≥140 or DBP ≥90

b. Intermediate → SBP 120-139 or DBP 80-89 or treated to goal

c. Ideal → <120/<80

7. Fasting plasma glucose, mg/dL

a. Poor → ≥126

b. Intermediate → 100-125 or treated to goal

c. Ideal → <100

For the diet pattern score, each of the following elements is given a score of 1:

• ≥4.5 cups/day of fruits and vegetables

• ≥2 servings/week of fish

• ≥3 servings/day of whole grains

• no more than 36 oz/wk of sugar- sweetened beverages

• 1500 mg/day of sodium.

Patients can be encouraged to keep track of their CV health and their progress over time. One way is by using apps such as the AHA app My Life Check which assesses people’s health with a questionnaire, then a score is given as well as recommendations to improve it. This can be accessed at https://mlc.heart.org/.

Discussing adverse effects and drug-drug interactions

In the same way benefits of statin therapy should be explained during the clinicianpatient discussion, potential adverse effects and drug-drug interactions should be discussed. One of the most frequently reported reasons for statin discontinuation is muscle-related symptoms, which affects <25% of patients.(14) However, if side effects are not severe, patients should be re-challenged since even with this history of statin intolerance, they can be successfully reinitiated on therapy. (15) This can be done either by starting the same or a different statin, decreasing the dose of the statin, trying alternate/ intermittent day statin dosing, with or without non-statin therapy in order to achieve maximal LDL lowering.(6,16) Additionally, switching to a hydrophilic statin such as rosuvastatin or pravastatin may be reasonable, as these seem to be associated with fewer statin associated intolerance symptoms.(17) New onset diabetes has also been reported, but this depends on the population, as it is more frequently seen in those who already have risk factors for diabetes mellitus, including metabolic syndrome, impaired fasting glucose, BMI >30kg/m2 , and/ or hemoglobin A1C >6.0% (6,18), with diagnosis being made as early as 5.4 weeks after initiating statin therapy. (18) However, this is not an indication to discontinue therapy (6) and considering the cardiovascular effects of statins, this benefit outweighs the small increased risk for new onset diabetes.(19) Other adverse effects that raise concern in patients and clinicians include transaminase elevations >3x the upper limit of normal which occurs infrequently (6), as well as memory/cognition issues which has been reported in case reports with no increase in memory/cognition problems reported in large-scale randomized controlled trials.(6) Women in particular tend to have greater risk for adverse effects compared to men, particularly glucose elevation and myalgias, which can be due to multiple factors including gender differences in body fat, muscle mass, comorbidities, polypharmacy, etc. (20), and clinicians should be aware of this.

Multiple drug-drug interactions exist between statins and several frequently used medications that can increase a patient’s likelihood to develop adverse effects. Because of this, it is very important to take the time to do a reconciliation of the patient’s medications in order to identify those that could potentially interact with the statin being considered. To aid with this, the ACC has created a tool, the ACC’s Statin Intolerance Tool, where one can compare the statin characteristics and possible interactions, and this can help identify possible drugdrug interactions and determine which statin would be the best option, as well as to determine if a patient is truly statin intolerant. This tool can be accessed at http://tools.acc.org/ldl. In the case of our patient, she was already taking amlodipine 10mg and gemfibrozil 600mg when simvastatin 40mg was initiated. This combination of medications could be the reason for her muscle symptoms, given that gemfibrozil is contraindicated in those on statin therapy since it is associated with increased risk for muscle symptoms and rhabdomyolysis and it should have been discontinued before starting the patient on statin therapy. Similarly, when patients are taking amlodipine, the dose of simvastatin should not exceed 20mg daily.

In those patients who are truly intolerant to statins, LDL-C lowering can be achieved with other non-statin medications. Nonstatin agents with evidence supporting their LDL-lowering effects include ezetimibe, bile acid sequestrants, and PCSK9-inhibitors, and they can also be used as add-on agents to statin therapy when further LDL lowering is required. (6) More recently, bempedoic acid, an inhibitor of adenosine triphosphate citrate lyase that lowers LDL-C by about 16.5% when added to maximally tolerated statin without adding a higher incidence of overall adverse effects(21), was approved by the FDA for the treatment of adults with heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia or established ASCVD requiring additional LDL lowering.(22) Although it has been described to be safe and efficacious in those with hypercholesterolemia and statin intolerance (23), its use has not been approved for that purpose, and ezetimibe, PCSK9-inhibitors, and bile acid sequestrants should be used first before considering this agent.

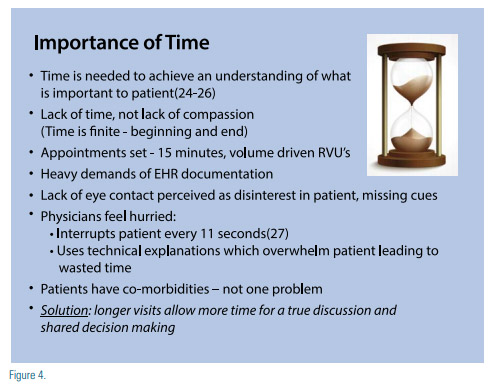

Time is an important commodity to the clinician and when well spent, can save lives by reducing cardiovascular risk. Patient engagement limited by time is not insurmountable, but a challenge that can be mastered in this day and age. Some of these impediments are noted in Figure 4.

Using a Checklist

Clinicians can use support staff to create a patient risk profile and challenges prior to the visit. In order to facilitate more time for clinician-patient shared decision making for initiation of therapy, the 2018 AHA/ACC Multisociety Guideline on the Management of Blood Cholesterol provide a checklist that the clinician may use (6) which includes:

• ASCVD risk assessment

• Using the ASCVD Risk Estimator Plus, assign the patient to a statin treatment group

• Assess other patients’ characteristics that influence risk

• Assess CAC if risk decision is uncertain and additional information is needed to clarify ASCVD risk

• Lifestyle modification

• Review lifestyle habits

• Endorse a healthy lifestyle and provide relevant advice, materials, or referrals

• Potential net clinical benefit of pharmacotherapy

• Recommend statins as first-line therapy for ASCVD risk reduction when TGs are <500mg/dL or in some cases <1000mg/dl

• Consider the combination of statins and nonstatin therapy in selected patients • Discuss potential risk reduction from lipid-lowering therapy

• Discuss the potential for adverse effects or drug-drug interaction

• Cost considerations

• Discuss potential out-of-pocket cost of therapy to the patient

• Shared decision-making is essential

• Encourage the patient to verbalize what was heard

• Invite the patient to ask questions, express values and preferences, and state ability to adhere to lifestyle changes and medications

• Refer patients to trustworthy materials to aid in their understanding of issues regarding risk decisions

• Collaborate with the patient to determine therapy and follow up plan

Conclusion

The best therapies are worthless if they are not utilized. Having a plan on how to approach patients is essential. This plan should include a personalized assessment of their cardiovascular risk, evaluation of other possible factors that could enhance patients’ risk, and deciding the role of further testing such as a CAC score, but the most important piece is the clinician patient engagement, in order to engage in a shared decision. If physician time and/or availability is an issue, a separate visit for this matter could be considered, or utilization of the health care team to further an understanding of risk reduction given that understanding can further improve compliance. Clinicians and patients need to row in the same direction to move forward, and then momentum starts with mutual respect and understanding.

Disclosure statement:

Dr. De Jesus has no financial disclosures to report. Dr. Mintz has received honoraria from Regeneron, Sanofi, Jansen, and AKCEA Therapeutics.

References

1. Virani SS, Alonso A, Benjamin EJ, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics—2020 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020;141(9). doi:10.1161/ CIR.0000000000000757.

2. Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ (CTT) Collaboration, Baigent C, Blackwell L, et al. Efficacy and safety of more intensive lowering of LDL cholesterol: a meta-analysis of data from 170,000 participants in 26 randomised trials. Lancet Lond Engl. 2010;376(9753):1670- 1681. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61350-5.

3. Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ (CTT) Collaborators. The effects of lowering LDL cholesterol with statin therapy in people at low risk of vascular disease: meta-analysis of individual data from 27 randomised trials. Lancet. 2012;380(9841):581-590. doi:10.1016/S0140- 6736(12)60367-5.

4. Salami JA, Warraich H, Valero-Elizondo J, et al. National Trends in Statin Use and Expenditures in the US Adult Population From 2002 to 2013: Insights From the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. JAMA Cardiol. 2017;2(1):56-65. doi:10.1001/jamacardio.2016.4700.

5. Colantonio Lisandro D., Rosenson Robert S., Deng Luqin, et al. Adherence to Statin Therapy Among US Adults Between 2007 and 2014. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8(1):e010376. doi:10.1161/ JAHA.118.010376.

6. Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/ AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline on the Management of Blood Cholesterol: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2019;139(25):e1082-e1143. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000625

7. Navar AM, Wang TY, Mi X, et al. Influence of Cardiovascular Risk Communication Tools and Presentation Formats on Patient Perceptions and Preferences. JAMA Cardiol. 2018;3(12):1192-1199. doi:10.1001/jamacardio.2018.3680.

8. Karalis DG, Wild RA, Maki KC, et al. Gender differences in side effects and attitudes regarding statin use in the Understanding Statin Use in America and Gaps in Patient Education (USAGE) study. J Clin Lipidol. 2016;10(4):833-841. doi:10.1016/j.jacl.2016.02.016.

9. Nanna Michael G., Wang Tracy Y., Xiang Qun, et al. Sex Differences in the Use of Statins in Community Practice. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2019;12(8):e005562. doi:10.1161/ CIRCOUTCOMES.118.005562.

10. Victor BM, Teal V, Ahedor L, Karalis DG. Gender Differences in Achieving Optimal Lipid Goals in Patients With Coronary Artery Disease. Am J Cardiol. 2014;113(10):1611-1615. doi:10.1016/j. amjcard.2014.02.018.

11. Kostis WJ, Cheng JQ, Dobrzynski JM, Cabrera J, Kostis JB. Metaanalysis of statin effects in women versus men. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59(6):572-582. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2011.09.067.

12. Lowenstern A, Navar AM, Li S, et al. Association of Clinician Knowledge and Statin Beliefs With Statin Therapy Use and Lipid Levels (A Survey of US Practice in the PALM Registry). Am J Cardiol. 2019;123(7):1011-1018. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2018.12.031.

13. Lloyd-Jones Donald M., Hong Yuling, Labarthe Darwin, et al. Defining and Setting National Goals for Cardiovascular Health Promotion and Disease Reduction. Circulation. 2010;121(4):586- 613. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192703.

14. Victor BM, Teal V, Ahedor L, Karalis DG. Gender Differences in Achieving Optimal Lipid Goals in Patients With Coronary Artery Disease. Am J Cardiol. 2014;113(10):1611-1615. doi:10.1016/j. amjcard.2014.02.018.

15. Nissen SE, Stroes E, Dent-Acosta RE, et al. Efficacy and Tolerability of Evolocumab vs Ezetimibe in Patients With Muscle-Related Statin Intolerance: The GAUSS-3 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2016;315(15):1580-1590. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.3608 16. Ward Natalie C., Watts Gerald F., Eckel Robert H. Statin Toxicity. Circ Res. 2019;124(2):328-350. doi:10.1161/ CIRCRESAHA.118.312782.

17. Toth PP, Patti AM, Giglio RV, et al. Management of Statin Intolerance in 2018: Still More Questions Than Answers. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2018;18(3):157-173. doi:10.1007/s40256-017- 0259-7.

18. Ridker PM, Pradhan A, MacFadyen JG, Libby P, Glynn RJ. Cardiovascular Benefits and Diabetes Risks of Statin Therapy in Primary Prevention. Lancet. 2012;380(9841):565-571. doi:10.1016/ S0140-6736(12)61190-8.

19. FDA Changes Label on Statin Drugs | National Lipid Association Online. Accessed July 8, 2020. https://www.lipid.org/ communications/news/other/fda_changes_label_on_statin_drugs.

20. Jacobson TA, Maki KC, Orringer CE, et al. National Lipid Association Recommendations for Patient-Centered Management of Dyslipidemia: Part 2. J Clin Lipidol. 2015;9(6 Suppl):S1-122.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jacl.2015.09.002.

21. Ray KK, Bays HE, Catapano AL, et al. Safety and Efficacy of Bempedoic Acid to Reduce LDL Cholesterol. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(11):1022-1032. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1803917.

22. FDA Approves Bempedoic Acid for Treatment of Adults With HeFH or Established ASCVD. American College of Cardiology. http%3a%2f%2fwww.acc.org%2flatest-in-cardiology%2farticles%2f2 020%2f02%2f24%2f10%2f09%2ffda-approves-bempedoic-acid-fortreatment-of-adults-with-hefh-or-established-ascvd. Accessed April 13, 2020.

23. Laufs Ulrich, Banach Maciej, Mancini G. B. John, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Bempedoic Acid in Patients With Hypercholesterolemia and Statin Intolerance. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8(7):e011662. doi:10.1161/JAHA.118.011662

24. Pieterse AH, Stiggelbout AM, Montori VM. Shared Decision Making and the Importance of Time. JAMA. 2019;322(1):25-26. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.3785.

25. Rotenstein LS, Huckman RS, Wagle NW. Making Patients and Doctors Happier — The Potential of Patient-Reported Outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(14):1309-1312. doi:10.1056/ NEJMp1707537.

26. Joseph-Williams N, Elwyn G, Edwards A. Knowledge is not power for patients: a systematic review and thematic synthesis of patientreported barriers and facilitators to shared decision making. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;94(3):291-309. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2013.10.031.

27. Singh Ospina N, Phillips KA, Rodriguez-Gutierrez R, et al. Eliciting the Patient’s Agenda- Secondary Analysis of Recorded Clinical Encounters. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(1):36-40. doi:10.1007/ s11606-018-4540-5.

.jpg)

.png)